EDUCATION CONTENT IN DISTANCE LEARNING BASED ON THE EXAMPLE OF A FIRST DEGREE PROFESSIONAL CERTIFICATION COURSE OF THE ACCOUNTANTS ASSOCIATION IN POLAND

Anna Kasperowicz, PhD, Assistant Professor

Wroclaw University of Economics, Poland

|

The rapid development of information technologies helped to develop a new form of education which is known as the distance learning or e-learning. This form of education is used at universities, in vocational education ,and also by the Association of Accountants of Poland (AAP) in the certification in the accounting profession. Designing e-courses and providing e-learning is a challenge for those responsible for the educational content, as well as software developers. The basis for the creation of the learning content within the AAP course of the first degree professional certification is defined in the Organizational and Program Framework for Professional Certification of accounting assistants. These were some major factors which impacted the selection of the e-course content. The order of the individual subjects was not adequate in relation to the objectives of the course realized in the form of e-learning. Therefore, the system implemented content has been adapted to the needs of the e-course which was presented in the form of mind maps. The main objective of the study was to describe the concept of ‘learning content’ in distance learning and demonstrate the process of constructing it taking as an example the content of the course prepared for the first level of professional certification by the Association of Accountants of Poland in the form of e-learning. For this purpose, analytical approach was used, supported by induction and deduction methods. Keywords: educational content, e-learning, distance learning. |

Introduction

The turn of the centuries has brought forth a broad application of information technologies (IT). Information systems, coupled with the advance of telecommunication technologies, have made the Internet part of everyday life for the information society (Nowak, http://www.silesia.org.pl...). This new model of society puts a strong emphasis on learning and education. The rapid development of IT has enabled the use and propagation of new forms of education, such as distance learning (Kużdowicz, 2007: 42–44). Those forms of learning are widely used in vocational training, also in the professional certification process implemented by the Accountants Association in Poland (AAP).

Content creation for distance learning purposes requires a specific approach, much different from the one used in traditional courses based on face-to-face contact between the participants and educators. Preparation of content for distance learning requires close cooperation between education experts responsible for the actual content and IT personnel involved in the process. This cooperation creates a natural tension between two opposing concepts. On the one hand, education experts insist on enhanced visualization and interactivity of the course content. IT personnel, on the other hand, strives to limit this trend, invoking the arguments of increased workload and cost.

Educational content prepared for the purpose of distance learning is typically based on the existing material, developed for the purpose of traditional learning. Traditional content is of a great value from the factual perspective, but should not be directly copied into new forms.

The educational content for the AAP course of the first degree professional certification is defined in the Organizational and Program Framework for Professional Certification of accounting assistants. The requirements presented in the Framework classify the content of the course, but the postulated structural order of the content is not adequate for distance learning purposes. For this reason, the structure of the course has been rearranged to meet the needs of the new form of learning.

This study aims to define the concept of educational content for distance learning purposes and present the process of content creation, based on the example of the first degree professional certification course of the Accountants Association of Poland (AAP) offered in the form of distance learning. For this purpose the analytical approach was used, supported by induction and deduction methods.

1. Definition of Educational Content

The process of education is understood as a sequence of conscious and deliberate actions of teachers and students, which is composed of two elements: teaching and learning (Okoń, 1998, p 133). Teaching is a planned and systematic work of the teacher with the students, which implies the production and preservation of positive changes in their knowledge, dispositions, their entire personality (Okoń, 1998, p 55). In its turn, learning is a process in progress, which is based on experience, knowledge and practice of new forms of behavior and activities and subject to changes (Okoń, 1998, p 134).

|

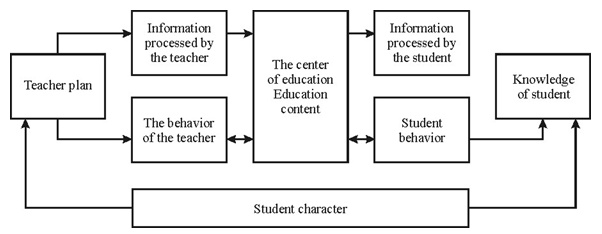

| Figure 1. The educational research scheme in e-learning |

| Source: Kruszewski K., Zmiana i wiadomość. Perspektywy dydaktyki ogólnej, PWN, Warszawa 1987, s. 81. |

In traditional education there are direct relationships between the two entities of the educational process, the teacher and the student. These relations called in the theory of teaching as ‘the educational research scheme’ include the processing of information as the basis of the research approach. The relationship formed between teacher and student during the learning process is a network of a direct mutual relationship. In the modern form which is e-learning there is an indirect relationship between the actors in the educational process, because between the two parties of the process there appears a new element, which is understood as a learning medium in which the educational content is available (Fig. 1). The exchange of information between the parties is possible exactly via this medium. The behavior of the teacher, as well as the behavior of the student, as part of the educational process is losing importance. The center of education is the most important part of the whole process as the element in which a relationship between the learning content creator – a teacher or a student, and the recipient is taking place. Despite the fact that there is no physical contact between the teacher and student there is a virtual contact via the Internet between them. This contact is initiated mainly by the student, which may be in the form of an e-mail to ask for an ongoing content. The questions asked give the teacher some clue how to implement the learning content of the system and show the direction of any alterations to the content of education (see Figure 1).

As it is shown in the scheme, the central element of education in distance learning is the learning center, which is the carrier of the content of education.

Educational content is a concept consisting of the following three elements (Kruszewski, 1987:112):

- an ordered repository of information – educational material,

- the sum of anticipated effects and experiences of course participants at the course location – i.e. a change in participant’s knowledge, skills and value system,

- the sum of educational situations aimed at changing the broadly defined and desirable changes in the participant’s personality and of spontaneous activities of the participant that lead to specific changes in mentality under the influence of educational material.

The first element is the educational material. For the purpose of distance learning, the material is arranged in several content layers. Those layers should reflect the structure of the educational material. Typically, distance learning content is arranged in a three-layer structure. Each layer should be accompanied by an attractive and concise description of its content. The first layer – i.e. the layer of the highest order – represents the advertising value. The second layer should present the content of the course. The third layer is used to present factual material and is also used to verify the acquired new knowledge or gain additional information. The most fundamental part of distance learning courses is represented in the content and forms of material included in the third layer. The content presented on screen can be referred to as a didactic message. The optimum message should be tailored to the following elements (Sokołowski & Skrzypniak, http://elearning.pl/filespace/):

- the message recipient,

- the message creator,

- the information contained in the message.

Before going into the process of content creation for a particular course, one should accurately define the target group, as well as situate the course material within the didactic process. One should decide whether the course is meant to supplement other content presented in a traditional form or to replace it. In the first case, when eye-to-eye contact with an educator is provided for, the main emphasis should be put on supplying content which serves to recapitulate and verify the acquired knowledge. Lecture-type content can be limited to minimum. The material should offer the user a chance to collaborate and validate the newly acquired skills in practice. In the second case, when the personal contact with the teacher is excluded, educational content should distinctly focus on lecture-type material.

Content creation is typically delegated to a team of experts, offering a close cooperation between educators responsible for the factual content and the IT personnel as message creators.

The literature describes 10 principles of training design, compliance with which the training efficiency can be increased. They have been shown and described in Table 1.

| Table 1 |

| Principles of training design |

| Lp. | Rule | Implementing rules for distance training |

| 1 | Tell appropriately selected evocative stories. | Using all the possible effects on the imagination. Supporting self-drawn conclusions. Maximum impact on the senses of hearing and sight. Using the examples in the form of short films, genre scenes. |

| 2 | Enabling learning through a play. | Breaking the monotony of converted content. Using games, fun games, both individually and in groups to coordinate discussions in chat rooms or message boards. |

| 3 | Let them experiment and learn from mistakes. | Equipping courses with interactive elements. Supporting learning from past mistakes without penalty. |

| 4 | Rightly choosing appropriate images and multimedia elements. | Multimedia effects should correspond to the transmitted content. With awareness of the technical limitations of the content should not be excessively expanded by the "special effects". |

| 5 | Surround the learner with the trainee care. | The person using the distance training should be supported from both technical and substantive with strict rules (specified time to respond and the form of support). |

| 6 | Give the opportunity to learn in a group. | Features of the course in not only communication mechanisms between users and manager of the course, but also between the people trained. |

| 7 | Focus on what is important. | Minimizing the message to the important one. |

| 8 | Give time for self-study and understanding. | The structure of the course should give time for one’s own work and conclusions. |

| 9 | ‘Infect’ the learner by your own passion. | Motivate participants to acquire knowledge. An interesting form, evocative transfer. |

| 10 | Make the trainee never stop learning. | Spread vision of the next steps in learning, create motivation to continue learning, support further enrichment of knowledge. |

| Source: Hyla M., Przewodnik po e-learningu, Oficyna Ekonomiczna, Kraków 2005, s.164–165. |

Thus, Table 1 describes the 10 general principles which should guide the creator of courses in the form of e-learning.

2. Professional Certification by the Accountants Association of Poland (AAP)

The Accountants Association of Poland (AAP) is an organization with long traditions, a direct successor of the Association of Bookkeepers in Warsaw, formed in 1907 and assigned a new name of the Union of Accountants in Poland in 1926. The present name – the Accountants Association in Poland (AAP) – was officially registered on 30 July, 1946. The first general assembly of the delegates of AAP took place on 18 May, 1958. From the onset, the association has actively supported the development of accounting and financial audit. Since 1907, it has always emphasized the utmost professional qualities and ethical standards of the profession.

One of the fundamental goals of the AAP is to propagate thorough professional knowledge among the candidates, as well as lifelong learning opportunities and promulgation of up-to-date procedures on local and international scale for the more advanced members of the profession.

Since May 12 1989, the Accountants Association in Poland has been represented in the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC) by the National Council of Chartered Accountants.

In 2009, the Main Board of the Accountants Association in Poland introduced the professional title of ‘certified accountant’ and initiated the certification procedures. Certification of the accounting profession is one of the conditions expressed in the International Education Standards of the IFAC. From that point, the AAP took up the task of vocational education for accounting professions, in line with international standards. It is also responsible for creating adequate conditions for upgrading professional standards of both AAP members and non-members working in accounting professions.

|

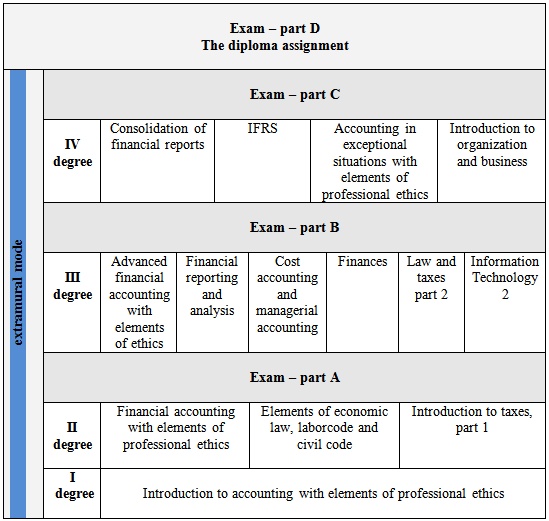

| Figure 2. Degrees of professional certification used in the Accountants Association in Poland |

| Source: http://www.dk.skwp.pl/Certyfikacja,prezentacja,5877.html |

Accounting is a profession of public trust, hence the requirements of professional and ethical standards are deemed of utmost importance. The educational path employed by the AAP is based on 14 modules divided into four degrees:

I degree – accountant,

II degree – accounting specialist,

III degree – chief accountant,

IV degree – certified (chartered) accountant.

Basic organization of the modules of professional certification by degree is presented in Figure 2.

Each degree of certification concludes with an examination conducted by an independent board. The examinations of the 1st, 2nd and 3rd degree are supervised by the regional examination boards. The 4th degree certification exam is conducted by the Central Professional Examination Board.

Each degree of professional certification is defined in a separate Organizational and Program Framework, with provisions pertaining to:

- the educational goal,

- preliminary requirements for course participants,

- knowledge and skills expected from participants at the end of the course,

- organization of the didactic process,

- methodology of education,

- the framework of educational program,

- detailed subject areas covered.

The subject areas covered in the first degree certification were used as the basis for the content creation for the purpose of distance learning in the educational path of professional certification realized by the AAP.

3. Content Creation Process in the Distance Learning Course of the First Degree Certification at Wroclaw Regional Branch of the Accountants Association in Poland (AAP)

As already mentioned, content creation for a distance learning course of the first degree professional certification at Wroclaw branch of the AAP was based on the subject areas defined in the respective Organizational and Program Framework for the candidates applying for the title of an accounting assistant. At the same time, it was assumed that distance learning as part of the education process would serve to supplement traditional training sessions conducted in person. For this reason, the content of the distance learning module would consist of interactive tasks designed to prepare the student for the final examination. The course participants would be expected to solve all the tasks provided in the module, after logging securely to a dedicated area of the web page. The IT system used for the content presentation was designed to allow for an instant verification. Answers provided by the user are compared with standard solutions. Wrong answers are automatically rejected, and the system displays an error message, providing a short timeframe for the user to correct the error. If the user fails to give a correct solution within that time, he or she may contact the course supervisor via electronic mail and request a leading question. After receiving the hint, the user is expected to solve the task without a further aid. Such an approach gives the user time to rethink the problem and make a correct decision. The leading questions should not hint at correct answers, but rather direct the user to respective sources of information, such as specific legislature.

The tasks are divided into 9 modules; each one starts with a content screen presenting an overview of theory (‘a crib’). The remaining content of each module comes in the form of interactive exercises. It is assumed that the content be presented in linear form, so that new concepts are first presented on a crib screen, and then introduced in specific interactive exercises. Each crib provides the basic elements of theoretical knowledge, accompanied by details of accounts required in solving individual exercises of the module. Special attention was paid to eliminate the risk of including elements of theory or accounts that have not been presented in the respective theoretical introductions.

The content creation was preceded by an in-depth analysis of the subject areas covered in the course. Detailed approach to this task will be explained on the basis of the example of a specific subject defined in the Framework, namely – point 1.8.1 ‘Record of fixed and intangible assets’. The context of the Framework provisions is presented below:

1.8 Record of balance sheet operations

- 1.8.1 Record of fixed and intangible assets

- 1.8.2 Record of stock, receivables and cash

- 1.8.3 Record of equity

- 1.8.4 Record of encumbrance

1.9 Record of financial result operations

- 1.9.1 Record of cost and operational expenses

- 1.9.2 Record of cost by type

- 1.9.3 Record of cost by source

- 1.9.4 Record of cost by type and source

- 1.9.5 Record of earnings before interest and tax

1.10 Record of cost and earnings from other operational activities

1.11 Record of cost and earnings from financial activities

In the course of factual selection of content, it was decided that this part of the first degree certification process will involve records of the four most important and fundamental operations realized in the context of fixed and intangible asset records, namely:

- Purchase,

- Liquidation,

- Sale,

- Depreciation.

Fixed asset purchase records require bookkeeping of two documents: an invoice and a commission document. To record these documents, the user needs details of three accounts: “2 – Accounts and claims”, “0 – Fixed assets”, and “3 – Resources and products” (the latter containing accounts of fixed asset purchases). Detailed description of accounts is contained in point 1.8.2 of the learning module, i.e. after the introduction of fixed assets. In order to properly record depreciation, the user should be acquainted with basic functions of cost accounts, which are introduced in a later part of the program, namely: in point 1.9.

In other words, realization of the subject “Record of fixed and intangible assets’ requires that the user be already acquainted with the subject of specific accounts, introduced in points:

- 1.9 Record of financial result operations in core business activities – depreciation,

- 1.10 Record of cost and earnings from other operational activities – liquidation, sales,

- 1.8.2 Record of stock, receivables and cash – sales,

- 1.8.4 Record of encumbrance – purchase.

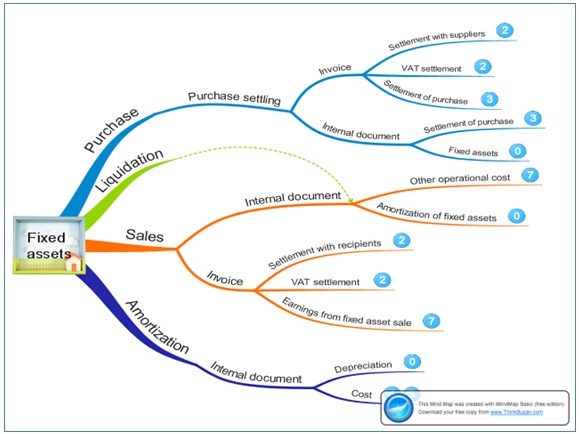

Hence, the order of content postulated in the Framework is clearly inadequate from the viewpoint of the adopted concept of content structure for a distance learning module. An ideogram of relations between economic operations, their documentation and, ultimately, accounts and account groups is presented in the form of a mind map in Figure 3.

|

| Figure 3. Mind map – interrelations between operations, documents and accounts in recording of fixed and intangible assets (author: Anna Kasperowicz) |

The structure of the correlations shown in Figure 3 is by no means linear. The above approach may be successfully used in a traditional (face-to-face) learning context, when the students are able to ask questions. Furthermore, this context offers teachers feedback to evaluate students’ comprehension and allows them to modify the content accordingly. In distance learning context, when the users (students) are required to solve the learning problems on their own, without guidance, this type of ‘content skipping’ should be avoided. Organization of content should be as fluid as possible.

Based on the above conclusion that the organization of content postulated in the Framework is not suitable for distance learning purposes, the following reorganization of content was adopted:

- Accounting – preliminary definitions. Characteristics of assets and liabilities;

- Balance sheet and profit-and-loss account;

- Economic operations and their impact on balance sheet;

- Books of account;

- Cost of core business operations;

- Settlements and core business operations;

- Other operational activities;

- Financial activities;

- Exceptional occurrences and calculation of financial result.

Points 1 to 4 cover the basic autonomous notions – in this case, the order of content presentation is not prioritized. Only at later stages of the education process, proper sequence of content is of fundamental significance, and should be realized in a linear order to warrant comprehension and accordance with the adopted concept of distance learning. As shown above, the linear structure of the content starts with the introduction of cost grouping in groups “4” and “5”. The precedence of cost in this approach stems from the fact that good comprehension of the notion of cost is needed to properly approach the detailed problems, such as core business and other business activities, and financial activities. The next module applies to settlements and core business activities, and introduces the concepts of purchase and sale of resources and goods, as well as VAT settlements. The notions of fixed and immaterial asset operations are introduced as late as module 7 of the distance learning course. Those can be safely introduced at that point, since the notions of cost, depreciation, settlement of sale, purchase and VAT required for proper comprehension of the subject have already been discussed in earlier modules. Hence, module 7 can be devoted solely to presentation of content directly related to fixed and immaterial assets.

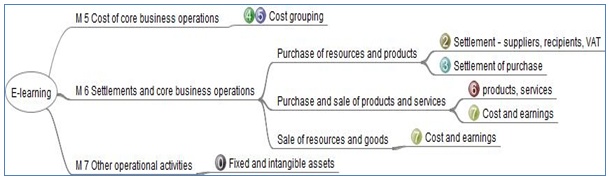

The division of modules five (M5) to seven (M7) with corresponding account relations is presented in Figure 4.

|

| Figure 4. Mind map – division of content into modules 5,6,7 (M5, M6, M7) (author: Anna Kasperowicz) |

The adopted approach to the content organization for the purpose of distance learning warrants continuity of discourse and creates conditions for independent realization of the learning material, without the need to resort to external sources of knowledge.

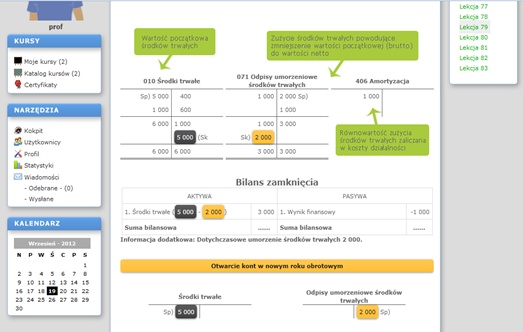

To complement the discussion of the problem under study, two samples of the distance learning application are presented below. These are excerpts from the module “other operational activities. Figure 5 presents a screenshot of the so-called ‘crib’ screen.

|

| Figure 5. A ‘crib’ screen taken from module 7 – Other operational activities, as used in the distance learning application of a first degree professional certification course for accounting assistants. |

| Source: learning.skwp.pl. |

The screen above shows a diagram of the interrelations between closing of financial year accounts, closing balance and opening of the accounts for the next fiscal year. The diagram is designed to help students tackle problems contained in the next part of the learning process.

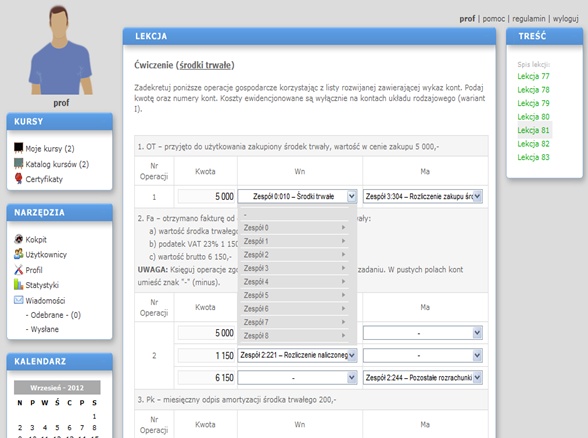

|

| Figure 6. Sample of content taken from module 7 – Other operational activities, as used in the distance learning application of a first degree professional certification course for accounting assistants. |

| Source: learning.skwp.pl. |

Figure 6 presents a sample exercise being used to cover fixed assets.

The sample screen shows part of an exercise for bookkeeping of economic operations. The exercise requires students to select proper accounts from a roll-down list.

Conclusions

Content creation for the purpose of distance learning is a laborious task of a great responsibility. It requires full comprehension of the factual knowledge covered in the e-learning course. The structure of the content employed in traditional courses, with a face-to-face contact between teachers and students, is typically unsuitable for distance learning purposes. In the case under study, the e-learning course preparation prioritizes factual linearity of content, which was not present in the respective provisions of the Operational and Program Framework of the first degree professional certification course for accounting assistants.

Bibliography

Arbeitszufriedenheit. In: Uwarunkowania jakości życia w społeczeństwie informacyjnym

Hyla, M. (2005). Przewodnik po e-learningu. Oficyna Ekonomiczna. Kraków

Kluge, P.D. & Kużdowicz, P. (2007). Nutzung dispositiver und ntscheidungsunterstützender Funktionalitäten von ERP-Systemen – Antrieb oder Bremse für die Entwicklung der. Tom 1. Uniwersytet Marii Curie-Skłodowskiej w Lublinie. Lublin

Kruszewski, K. (1987). Zmiana i wiadomość. Perspektywy dydaktyki ogólnej. PWN. Warszawa

Nowak, J. S., Społeczeństwo informatyczne – geneza i definicje http://www.silesia.org.pl/upload/Nowak_Jerzy_Spoleczenstwo_informacyjne-geneza_i_definicje.pdf

Okoń, W. (1998). Wprowadzenie do dydaktyki ogólnej, wydanie IV. Warszawa

Sokołowski, S. & Skrzypniak, R. Zasady konstruowania treści nauczania w kształceniu na odległość, http://elearning.pl/filespace/artykuly/SokolowskiSkrzypniak.pdf. [Accessed on: 12/01/2012]