COMPETITIVENESS – A KEY TO BUSINESS VIABILITY

Cem Gucel, PhD

Turkish Armed Forces, Turkey

Suat Begec, PhD

Cag University, Turkey

Strele Iveta

Turiba University, Latvia

|

Whatever the size, enterprises is the driving force of economic growth in general. Policy makers in Europe and beyond its limits invest heavily to create a business-friendly environment and to ensure business viability. There is no single success formula for such a complex process like running of business activities or creating a quality business environment. Both, standards of quality requirements and quality criteria as such may vary in different contexts and under interaction of different internal and external factors, and change over time. This is why competitiveness should be taken into account as one of the key aspects of business viability when assessing the overall quality of business environment. The aim of the study is to explore – based on survey questionnaire data of 790 general managers of various enterprises – competitiveness as the core factor ensuring viability and quality of Latvian business environment, and to identify directions of business strategy decision-making which is important to enterprises, as well as provide information on the quality of the Latvian business environment to business policy makers, investors and the general public, both in Latvia and abroad. The task of the research is to analyze theoretical background of competitiveness, assess competitiveness of Latvian businesses, and analyze the obtained results. The study addresses and analyses the availability and usage efficiency of resources including human resources, physical resources, and financial resources, corporate strategies, internal and external communication networks, external environment effect on competitiveness, as well as the company's financial performance over its competitors. The study applies monographic, questionnaire survey and graphical method. Keywords: competitiveness, business viability, factors affecting competitiveness, efficiency, management. |

Introduction

It is believed that business talent, human creativity, abilities and skills that can be used for business are inherent practically in all the world's nations. However, the fact how many or few companies, whether domestic or foreign market-oriented companies, and whether service or manufacturing companies will start and will be able to successfully develop their business in the specific country and time period, to a large extent will depend, first, on the ability of particular people to put creativity, skills and talent into practice. No less important are the so-called external factors, such as business law, access to finance, simplicity of bankruptcy procedure, the different levels of corruption is what is commonly referred to as business infrastructure quality. Considering those two factors as a whole: the quality of the general business environment can be judged by the quality of business infrastructure and the human quality, i.e., business knowledge and skills of the current and prospective entrepreneurs, and their ability to employ these faculties in the business practice. In other words: what national or regional business viability is. In this context, the term “viability” has three main, complementary, meanings. First, the “viability” stands for the significance, importance, and the extent to which interaction of the above factors enable business to contribute to the overall national economic growth. Business contribution to economic growth, in turn, is closely related to another interpretation of the term “viability”: power, innovation, business health. It is about resources available to businesses, such as quality of human, physical and financial resources, corporate strategies, etc. factors as a whole directly responsible for business viability and ability to grow. Third, the “viability” is dynamic, the ability to change, adapt, and versatility. Given the above explanations of the term “viability”, the aim of the study is to explore competitiveness as the key factor determining the Latvian business environment. The main target audience of the study is general amangers and owners of 790 randomly selected companies, both – those who have already achieved remarkable success in the local and international markets, and those who have just started their activities. The study was conducted as phone interviews; information on companies was selected using ORDI database, which is maintained by BureauVanDijk. The methodology of this survey, including the questionnaire, was produced on the basis of the methodoly developed by Dr. Arnis Sauka (SSE Riga, Latvia), Prof. Dr. TomaszMickiewicz (University of London, United Kingdom) and Dr. UteStephan (Leuven Catholic University, Belgium). The survey was conducted using a questionnaire built of six sections.

The study applied monographic, questionnaire survey and graphical method.

1. Competitiveness of Enterprises

It is important to define what we mean by competitiveness, namely, the specific criteria that a competitive enterprise should meet. Business theories which are nothing but a carefully groomed corporate experience across a range of countries and time periods, do not provide a definite answer as to why a company will always be more competitive than others. It is only logical, because a company's competitiveness is affected not only by the specific factors, but also by the combination of these factors, which further depend on many other factors: such as the external environment, time, and success. Such combinations of factors, just like business processes in general, tend to be not only complex, but also not always logically explained.

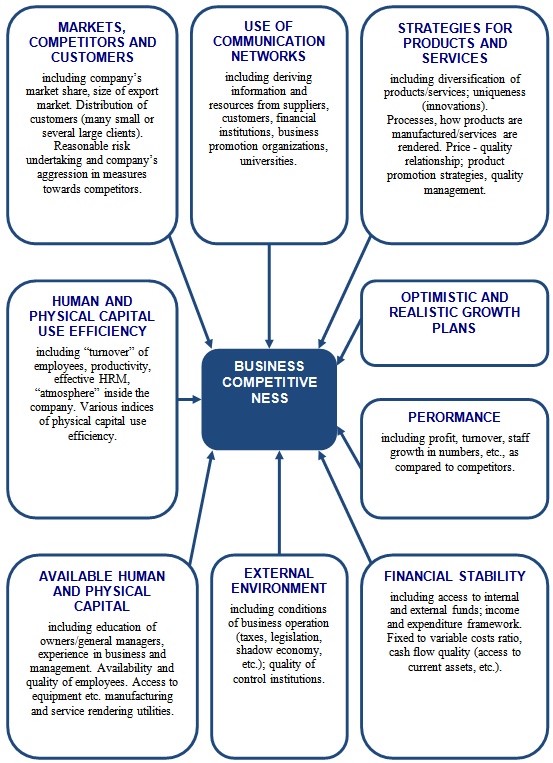

Therefore competitiveness is not only hard to define, but also extremely difficult to measure: as is known, the know-how having brought success to some company might not be that useful to other companies due to various additional influential aspects. Business studies in various countries have identified a number of factors that, individually or by using different combinations, have the potential to promote a competitive business. These factors are summarized in Figure 1. The aim of this chart, like the aim of the study, is to identify the key factors in ensuring the competitiveness of enterprises. Presented in Figure 1, importance of the factors influencing the competitiveness may vary depending on, for example, the size or the field of activities of the enterprise. It is impossible to envelop assessment of all the factors listed in the Figure 1 in just one survey. The study analyzed the most relevant factors influencing competitiveness of Latvian enterprises: availability and usage efficiency of resources including human resources, physical resources, and financial resources, corporate strategies, internal and external communication networks, external environment effect on competitiveness, as well as the company's financial performance over its competitors.

|

| Figure 1. Factors determining business competitiveness. |

| Source: the authors based on review of entrepreneurship literature. |

The section one of the guestionnaire consisted of several questions aimed at learning about quality of human resources available to a company, and the efficiency of how the company uses these resources to operate the business. Quality of human resources and usage efficiency thereof is, definitely, one of the most substantial factors in building competitiveness of any company. For example, a range of studies in various countries (Man et al, 2002; McKelvie & Davidsson, 2009) indicate that competitiveness of business depends directly on productivity, motivation and loyalty of employees available to an enterprise. Generating of new ideas often coming also from the companies’ employees is one of the factors improving business competitiveness through providing of innovations (Subramaniam and Youndt, 2005). Similarly, skills of employees in rendering high-quality service to clients, and ability to sell products or services have direct effect on financial performance of the company (Hitt et al., 2001; Rauch, Frese and Utsch, 2005). Moreover, in order to ensure competitive business operations, especially for companies whose success is attributed to time-consuming and major investments in staff training, optimum employee rotation is fundamental (McKelvie and Davidsson, 2009). In the survey, general managers or owners of companies were offered to assess their employees on a 1-to-7 rating scale where “1” implied a very poor situation whereas “7” corresponded to a competitive company in terms of availability of human resources and efficient employment thereof. The section one of the questionnaire included also questions on staff training in the company, and we also asked general managers and owners of the companies to assess availability of other no less important resources, as well as information technologies and any technical equipment essential in ensuring the company’s competitiveness. There is no doubt that people running the company, i.e. the owners and the managers, play a great role in ensuring of business competitiveness (Alvarez and Busenitz, 2001).

In order to better appreciate business competitiveness in relation to this aspect of human resources, a range of questions were included in the questionnaire to assess quality of the owners and the managers: degree of education, and the previous business experience. Many studies have revealed that higher level of education (Hambrick and Mason, 1984; Bantel and Jackson, 1989), and long- standing business experience (Helfat and Lieberman, 2002; King and Tucci, 2002) of owners and managers influence the company’s performance and the company’s competitiveness remarkably and positively (Davidsson, 2006; Gimeno et al, 1997).

The section two of the questionnaire addresses very important business processes ensuring business competitiveness, in a relative detail: corporate strategies. Based on competitive business theory of M.Porter, the questionnaire proposed company owners and managers to assess the corporate strategies regarding price leadership, distinction (i.e., offering of high value-added products or services) and focussing on specific target markets. Rating scale between 1 and 7 was used. The companies which appreciated their current business strategy toward the rating “7”, as per the business theories, should be more competitive over the companies giving the rating closer to “1” (Knight and Cavusgil, 2005; Mudambi and Zahra, 2007; Hamermeshetal, 2002; Gilley and Rasheed, 2000). The guestions 5 to 7 of the survey questionnaire continue analysis of the corporate strategies from the so called aspect of business orientation being a research tool widely employed in literature. This instrument is used to assess three business strategy elements fundamental for a company’s competitiveness: innovations, undertaking risks, and proactivity in measures aimed at competitors (Covin and Slevin, 1989; Miller, 1983). As per earlier studies done in different countries (Baker and Sinkula, 2009; Huges and Morgan 2007; Kreiseretal, 2002; Moreno and Casillas, 2008; Short, et al., 2009; Rauch et al, 2009), the companies having their business oriented to innovations, taking risks and proactivity feature higher competitiveness, on the whole.

When analyzing competitiveness of a company, not only current achievements should be taken into account, but also ability of general managers and owners of the companies to assess and prevent the possible bottlenecks in the business operations (Man et al, 2002). The survey questionnaire included a question asking the respondents to assess business priorities in implementation of different processes substantial for business competitiveness. The survey questionnaire also included questions on the company's export volumes in order to explore the extent to which companies focus on domestic or foreign markets, which is another very important aspect of business competitiveness (Roper, 1998; Ibeh, 2003).

Beside the company's internal resources, a crucial role is played also by the extent to which the company is capable of outsourcing so that to implement a successful business strategy and thus raise competitiveness. As often as not, these are resources that are obtainable free of charge or through relatively little investment of funds and time. For example, such competitiveness-enhancing resources include information that companies can get from suppliers, customers, and competitors; cooperation with organizations engaged in promoting of business, such as generation of new contacts or entering new markets, collaboration with universities and research institutes for development of new, innovative products and services, etc. (Robson and Benett, 2000; Hoang and Antoncic, 2003; Greve and Salaff, 2003). With a view to find out the extent to which Latvian companies use a variety of communication channels, which, in turn, eventually provide access to various resources enhancing competitiveness, the questionnaire included also a section: Communication Networks.

While highlighting the role of human resources, business strategy and communication networks, one should not forget one of the most important aspects to ensure any business activities and competitiveness – access to funds and efficiency of spending thereof (Pissarides, 1999; Bechetti and Trovatto, 2002; Bougheas, 2002). This factor of business competitiveness is analyzed in detail in the section four of the study questionnaire.

The section five of the questionnaire provides assessment of external environment factors affecting business competitiveness, namely, the extent to which business owners and managers consider that the markets in which the company is engaged are favourable for business activities (Dess and Beard, 1984; Miller and Friesen, 1982). Whereas, in the section six, the company owners are asked to assess growth of the company: both from financial and social aspect, thus showing the extent to which the particular company has been able to create value for themselves and for environment by the current resources, and how good the company was in this field in comparison with competitors (Sauka, 2008).

2. Major Factors Affecting Competitiveness of Latvian Companies

2.1. Human Resources and Efficiency Thereof

Most entrepreneurs, regardless of the company’s size or the sector they represent, would agree that employees are the bedding of business success and competitiveness. Summarized results of the study reveal that, all in all, general managers and owners of Latvian companies are rather satisfied than dissatisfied with the quality of their staff. Such crucial aspects of business competitiveness like willingness of employees to stay long-term with the company, product and service selling skills, serving to clients, generating new ideas, staff productivity, motivation to work as well as loyalty were rated between 5.9 and 6.2 within the 1-to-7 scale (where “7” stands for highly competitive quality of human resources). Probably, one of the most effective ways to improve and sustain a sufficiently high quality of staff is investing in staff training. The survey’s results show that, in this respect, Latvian companies are fairly active, i.e., something over a half of the surveyed companies have provided training to their employees during the recent year with a goal to improve their skills in production of goods and providing services.

Earlier business studies indicate that, beside the staff efficiency, also the degree of education and previous business experience of owners and general managers of the companies play a great role in ensuring of business competitiveness (Alvarez and Busenitz, 2001; King and Tucci, 2002). These two factors are vital to micro- and small enterprises where owners and managers of the company are the only available human resources. Despite the different roles of the owners and the managers, there is no doubt that education and skills of general managers of the companies are very important also in large enterprises. Results of the Latvian business competitiveness survey, like other studies conducted in Latvia (Sauka, 2008; Baltrušaityte-Axelson, et al, 2008), indicate a high, and even very high educational level of company managers. Almost 60% of the surveyed owners and managers of Latvian companies have a Bachelor’s Degree, while 28% thereof have Master’s Degree. In interpreting this result, one should take into account also the quality of the obtained education, which, in turn, cannot be properly evaluated in this type of study, when company managers and owners are interviewed. As regards experience of managers and owners of Latvian companies, the survey results indicate that 49% of the surveyed respondents have had been engaged in business or business administration also before starting the particular business. Giving that such experience (either good or bad) usually serves as a basis for successful future business, especially when market and rules of the game have been defined, or even funds have been raised and contacts have been collected (see Helfat and Lieberman, 2002), a conclusion can be drawn that background of Latvian entrepreneurs is sufficient at least, so one can hope for competitive performance of the current businesses.

2.2. Business Strategies

A strategy, first of all, is related to customer care – the main source of income for the business. It is reasonable to assume that, especially for those companies whose material base is not sufficiently stable, it is too risky to focus on just one or two major customers in order to share optimal risks, especially in the long run (Simon, 2011; Roper, 1999). In such cases, the focus on narrow circle of large companies most often implies also bulky orders. However, this is why small and medium sized enterprises, especially, have to reckon with strong dependence on very specific requirements of such clients as well as changes in these requirements, for instance, due to changes in market conditions, or as a result of technological progress, etc., that often may lead to bankruptcy.

Although business theories do not give a clear answer as to the optimal amount of clients to be served, however, business growth, especially in the long run, largely depends on orientation of business strategies to small yet relatively many clients. Experience of many companies show that such a strategy provides more stable and predictable income and, in the case of small and medium sized enterprises, it can ensure building a sufficient resource base so that to eventually afford taking a risk in working with large, and even very large customers (Zahra and Covin, 1993; Sauka, 2011; Simon, 2009).

Results of survey on Latvian business competitiveness reveal that, on the whole, Latvian entrepreneurs are found to be in the middle in terms of choosing the element of this strategy (rating of 4.5 out of 7), which, conditionally, may be considered as relatively good. All in all, the Latvian companies take care of their existing customers. According to the survey, the majority of customers of Latvian enterprises are regular customers (rating 5.9 out of 7), that is, of course, essential to sustain competitiveness of the companies.

Business theories also point to the fact that, especially in the long run, one of the elements raising competitiveness is the ability to diversify the range of the offered products or services (Wright et al, 1995; Simon, 2009). A number of success stories, including Latvian companies working in international markets (Sauka, 2011; Sauka and Welter, 2011), demonstrates that through diversifying the range of products the companies are able to be independent from drop of sales of one product, which, of course, is essential to raise competitiveness. According to evidence of Latvian business competitiveness survey, Latvian companies, in general, show just a slight trend to opt for a business strategy built on diversified range of products and services (rating 4.8 out of 7).

Experience of entrepreneurs gathered from various earlier studies also indicate that the most successful, fastest-growing companies are those who, instead of “trying to serve all”, focus on and are able to become leaders in a relatively small market segments or niches (Simon, 2009, Sauka and Welter, 2011; Sauka, 2011). Focusing on specific market segments generally provides a better contact with clients, and thus a better knowledge and understanding of clients' needs and the opportunity to meet them, which, undoubtedly, is one of the prerequisites for a competitive enterprise. M. Porter defines such business strategy orientation as “focus strategy”, which, according to Porter (1990), is regarded as one of the three possible success strategies for business competitiveness. In turn, the results of survey on Latvian business competitiveness show that the strategy of Latvian businesses is also based on a slight inclination to focus on the target market segments (rating 5.2. out of 7).

In addition to “Focus Strategy”, the study also included two other strategic elements, very important for business competitiveness: cost optimization and focus on developing of high value-added products or services. M. Porter defines such business strategy focus as “price leadership” and “distinction” where the first case, companies would endeavor to take all possible measures to reduce the cost of goods or services, thus ensuring competitiveness through either lower prices or higher profits. In case of “distinction”, in turn, competitiveness of enterprises will be based on products or services, preferably hard to copy or replace, with comparatively high added value for which the customer would be willing to pay a higher price (Porter, 1990).

As per results of Latvian business competitiveness survey, judging by the average indices, Latvian companies do not tend to use either “price leadership” or “distinction” strategy very strongly. The average rate of cost optimization elements such as outsourcing, standardization of products, and increasing of production capacities, range between 4.3–4.6 out of 7. Moreover, companies do not strive to offer high value-added product or service (only 3.6 out of 7). Thus, taking into account the average indices, it can be concluded that companies are likely to choose “something in between” these two strategies without strong focus on either the price leadership or generating of high added value.

However, in order to draw these conclusions one cannot rely just on the average rates. It is important to know how the particular rate forms, and this, in turn, requires an in-depth data analysis. This data analysis is important because the average rate allows judging on corporate strategies on the whole, rather than identifying which particular strategies are chosen to be implemented to a greater or lesser extent by certain surveyed groups of enterprises.

Data gathered in analysis of individual groups of enterprises, shows that approximately the same number of surveyed Latvian companies choose or are forced to combine a relatively high cost with low value-added products or services offered on the market (the “cost leadership” and “high added value” was appreciated between 1 and 3), or to combine average costs with an average added value (both aspects of the strategy were rated at 4). It, definitely, cannot be spoken of highly competitive business operations either in one or the other case, but especially in the case when a part of a company works with high costs while offering low added value.

One third of the Latvian companies, however, prefer to offer products of a relatively high added value at low cost. Although, according to M. Porter, choosing combination of these strategies, i.e. “distinction” and “price leadership”, is not desirable and, in the long term, can lead to a decline in the business competitiveness, the market, however, witnesses cases when companies are able to achieve very successful results by offering high quality products at low cost (Sauka, 2011).

As per summary of the survey results, Latvian companies able to offer high added value at low costs are in the minority as compared with the two other above-mentioned groups of companies. In general, the study results suggest that, although some companies tend to use benefits of the “focus strategies”, and give a relatively better assessment of the quality of available human resources and access to physical resources, competitiveness of Latvian enterprises can not be regarded as positive due to disequilibrium of the costs and added value. The reason does not lie in “voluntary choice” of the companies, but rather in application of such strategies “under compulsion”, as soon. The cause of high-costs, regardless of the added value of the products, might not be inefficiency of entrepreneurs in operating their businesses, but rather high production and service costs resulting from, for instance, technologies, buildings, etc. acquired at high prices between 2006 and 2007.

In addition to the above factors affecting competitiveness of Latvian enterprises, the survey questionnaire also included some other element essential for business competitiveness – “business orientation”. Business orientation is a tool combining three strategic dimensions vital to successful operation of companies, allowing measuring the extent to which companies focus on innovation, performance, risk-taking, and proactivity. A number of studies conducted in different countries prove that companies which are more innovative, take higher risk yet a well-considered risk at the same time, and are more active in their measures towards competitors, show much better performance and hence are more competitive (Moreno and Casillas, 2008; Short, et al., 2009; Rauch, et al, 2009).

According to the results of Latvian business competitiveness survey, the overall rate of innovativeness of Latvian companies, fluctuate between 3.4 – for ability of the companies to create new, unique production processes and methods, as well as fundamental changes in the products or services, and 3.9: introduction of new products or services, in 1–7 rating scale, where “7” stands for an innovative company. Consequently, taking into account the results of the study (the average index), the general innovation level of the Latvian entrepreneurs can be regarded as slightly below the average rate that is less than 4, in 1–7 rating scale.

Similarly to the cases of companies' price leadership or distinction strategy, it is essential to understand how this average rate forms, too. It is important to understand whether the innovation rate of the majority of Latvian enterprises is really close to the mark 4, or the average index emerges when a part of the Latvian entrepreneurs assess the level of innovation close to the mark 7, and as many again appreciate the same close to 1.

The survey procides the answer to this question by showing the following trends: first, as regards introduction of new products, a large majority of Latvian companies evaluate this indice at either “1” (very low innovativeness, about 27% of respondents) or “5” or “6” (relatively high innovativeness, 17% and 23%, respectively). Therefore, it can be concluded that, for introduction of new products, the vast majority of Latvian companies are relatively innovative.

According to the results of this survey, similar average rates, like in the case of the company's innovation, are shown in terms of risk-taking aspect of business orientation, that was rated between 3.5 and 3.6 in the 1–7 rating scale. A slightly better average index (i.e. 4, within the 1–7 scale) is reached only in relation to the question, “the company aims to be ahead of the competitors by introducing new ideas and products.”

Having analyzed how the average index arises, we conclude that, in contrast to innovativeness, risk-taking factor of business orientation does not approach typically to either “1” or to “7” for the Latvian companies. Rather, the assessment is focussed closer to the mark “4” with tending towards 1–3 of the scale. Similar conclusion with regard to the assessment of the concentration around the mark “4”, can also be drawn in terms of the proactivity factor of business orientation, where the assessment tends towards direction of 5–7 a little. Although this result, definitely, can not be considered as a strongly negative one, unfortunately, as demonstrated by experience of other countries (Rauch et al, 2009), it neither can be spoken of high competitiveness (in this case, for a Latvian company) at such orientation of the strategy. Thus, in accordance with the results of the Latvian business competitiveness survey, it would be suggested for Latvian companies to reconsider that it would be worth taking a little more risk and be more aggressive in competitors-oriented activities to improve the company’s position in either domestic or foreign markets.

In addition to the assessment of current strategy, the general managers and owners of the companies were also asked about the main priorities, which, to their opinion, the business should implement in order to compete effectively in the market. Summary of the responses reveales that the Latvian entrepreneurs think, the most important priority is to increase profits (5.8 out of 7), increase sales in the Latvian market (5.2 out of 7), reduce costs (5.0 out of 7), improve product or service quality (4.8 out of 7).

Finally, when analyzing corporate strategies, certainly, orientation of the companies to foreign markets, i.e. export volumes, cannot be omitted. The responses to this question of the survey suggests that 12–13% of Latvian companies are exporting between 5–25%of total sales, and as many again, i.e. 26–50% of total sales. For their part, ca. 6% of the respondents achieve export volumes up to 51–75% (6.1%) and 76–95% (6.4%). Admittedly, this looks like a very good and promising trend for business competitiveness. Therefore, according to the results of the Latvian business competitiveness survey, in relation to other elements of the business strategy, both thefocus on "price leadership" or "distinction" and "risk-taking" and "proactivity" – at least for a part of the Latvian companies it would be particularly appropriate to review these strategies, thus increasing opportunity of successful competing in the export markets, too.

2.3. Communication Networks

As is known, internal resources of a company, especially for small and medium sized enterprizes, are vcery limited pretty often. This is why successful companies attract different resources so as to compete on the market more effectively, moreover, the outsourcing is done at minimum investments, or without any pay at all. One of the not only most effective, but also the cheapest ways to involve the external resources required for competitiveness is to use successfully the contacts available to the company, in other words, communication networks.

The communication networks can be used in order to obtain very diverse types of resources important for company’s competitiveness (Malecki and Veldhoen, 1993; Simon, 2009). For example, successful and fast-growing companies across different coutries, including Latvia, have proved that a useful and often free information on the possible market trends such as products which are in demand or slow-moving in particular markets, “fresh winds” in relation to products, services, etc., can be derived from suppliers, customers, and competitors, too (Simon, 2009; Sauka and Welter, 2008; Sauka, 2011). As summary data of the Latvian business competitiveness survey shows, Latvian entrepreneurs do not tend to actively use neither this one (the average rate 3.9–4.4 out of 7), nor other communication networks. According to the survey results, the Latvian companies are especially inert in: cooperating with business incubators (1.6 out of 7), universities and scientific insitutes (1.4 out of), which could be potentially used as a resource to introduce an innovative, competitive product or service; cooperating with business promotion organizations – both public agencies (such as the Investment and Development Agency of Latvia) (1.9 out of 7), and non-governmental organizations (such as the Latvian Chamber of Commerce and Industry) (1.7 out of 7), which, for their part, might be used not only to influence business policy processes in the country (e.g., business legislation), but also to develop in foreign markets. The surveyed Latvian companies cooperate markedly little in free or cheap outsourcing with municipalities (1.9), banks and other financial institutions (2.5 out of 7), as well as friends and the family (2.5 out of 7). Relatively more, like in the case of customers, competitors, and suppliers, the Latvian companies used business press (4.2 out of 7) and the Internet (5.4 out of 7) to gather information vital to their businesses.

2.4. Financial Resource

In order to introduce competitive strategies, definitely, it is not enough just to use free or relatively cheap cost of communication network. Very important role in making use of business competitiveness, of course, is played by financial resources available to companies. According to data of Latvian business competitiveness survey, Latvian entrepreneurs evaluate access to financial resources as slightly above average. However, looking at the distribution of responses across company groups, it can be concluded that a slightly higher proportion of the surveyed Latvian entrepreneurs are satisfied with the availability of financial capital. According to the study results, about 50% of the surveyed companies rated access to the financial capital between 5 and 7 points (where “7” stands for fully sufficient access to financial resources). In turn, the assessment stood between 1 and 3 for slightly over 30% of the respondent companies. Although at large, this is certainly not a good index, it cannot spoken of Latvia as a business environment in which companies would have good access to the necessary financial resources; however, it should be admitted that, in the face of the general situation in the Latvian economy, this result should not be regarded as bad. The Latvian business competitiveness survey also included a question so as to measure whether the Latvian companies are able to make efficient use of the available finance capital (as well as human resources, physical resources, strategy, etc.) to gain profit. There was a desire to find out what is done with this profit. In relation to these indicators, the survey results are relatively good. Slightly over 72% of the interviewed entrepreneurs revealed that they had made profit the previous year. Moreover, about 70% of these companies reinvested the entire profit back into the business, which is clearly indicative of a long-term vision and that can attract the Latvian and foreign investors and prospective cooperation partners.

2.5. External Environment Impact

The research results indicate that, all in all, the surveyed entrepreneurs do not assess the impact of external environment on the business competitiveness either positively or negatively. Taking the average, we can conclude that the Latvian entrepreneurs consider that the effect of the external environment is neither too burdensome, nor threatening, nor contributing to business (rate 3.6–4.0 of 7). Looking at the results of the study in a bit more detail, however, we see that a slightly higher proportion of entrepreneurs consider the market risky, since each decision can be crucial, (i.e. ca.22% and 36% of respondents assess this aspect, respectively, at “2” and “3”). A similar bad trend is also shown in entreprenuers’ assessment of the dynamic nature of the market, inconsistency; most entrepreneurs also tend to see the market as ill-disposed, where it is hard to survive.

According to the results of this survey, there is a relatively little positive trend observed in Latvian entrepreneurs’ assessment of the market situation in terms of market growth in demand for products offered. However, despite the worse trends above, about half of respondents hold the view that the market has the potential, i.e., there are increasing business growth opportunities.

2.6. Business Activities Compared to Competitors

The owners and general managers of the companies were asked to assess performance of their business in comparison with the major competitors in the industry. The entrepreneurs were prompted to make such a comparison for the three key business performance indicators: profits, turnover and number of employees, as well as exports volume and value of investments made into the business.

The surveyed Latvian entrepreneurs assess their operations quite a bit below the average as compared to the competitors (3.7–3.9, depending on the performance indicator). So, judging by the average rating, Latvian entrepreneurs are doing no better or worse than competitors, on the whole. After analysis of the results in a little more detail, it appears that the majority of respondents (39–41%, depending on the performance indicator) put their activity on a scale of "3" compared to the competitors – so they still believe that competitors are better. This result of the study on competitiveness of Latvian enterprises, certainly, raises the question: what these companies are: Latvian or foreign ones, large or small ones, which, according to the respondents, outrival them. Unfortunately, the study on competitiveness of Latvian enterprises does not give an answer to this question. This is why the authors of the present study hope that other researchers will also focus on these and other issues related to detailed cognition of factors affecting competitiveness of Latvian enterprises.

Conclusions

A sign of business vitality is, undoubtedly, the willingness to adapt and change. Nowadays, when everything can be copied, one must constantly seek for its own distinguishing mark and be one step ahead of their ideas, innovations, and with service. In circumstances of severe competition, Latvian entrepreneurs therefore need to be particularly vital – to increase their productivity, competitiveness, recognizability, conquer new markets, and expand the range of partners to attract foreign capital and support of prospective investors in order to increase their own attractiveness and make contribution to the business environment in general.

The survey showed that Latvian companies so far have not sufficiently clearly defined their strategy for price leadership and generating of a high added value. The companies choose something in between, a combination of relatively high cost and manufacturing of low value-added products, thereby virtually excluding significant opportunities to compete globally.

Studies indicate that the Latvian manufacturers assess their competitive capacity higher than service providers and traders do. Competitiveness of manufacturers is based primarily on more successful choice of business strategies. Manufacturers have a wider range of regular customers, a diversified choice of products; and manufacturers appreciate their level of innovations at about 23% higher than other companies. Manufacturers have proved their greater willingness to take risks and to make efforts to stay ahead of their competitors.

Fear of risk, unwillingness to cooperate, a clear focus on a single business strategy, as well as lack of innovative products and too high costs of relatively low value-added products prevent Latvian companies from achieving the desired results in the competitive rivalry.

The cause of high-costs, regardless of the added value of the products, might not be inefficiency of entrepreneurs in operating their businesses, but rather high production and service costs resulting from, for instance, technologies, buildings, etc. acquired at high prices between 2006 and 2007.

Latvian entrepreneurs are well-educated – nearly 60% of the respondents have a bachelor's degree, but 28% have master's degree, while 40% have previous business experience. Similarly, the entrepreneurs highly appreciate the skills of employees to sell products and services, to serve customers, their involvement in promotion of new ideas, as well as productivity, motivation to work and loyalty, the total assessment standing at 5.5 points out of 7.

40% of entrepreneurs assess their individual performance as innovative, but all in all Latvian companies’ ability to innovate by creating new, unique production processes through introducing of new products or services, or making any significant changes, were rated as mediocre. Similarly, Latvian entrepreneurs are modest and self-critical at comparing their activity with a competitor performance. The most frequently – 40% of the cases – the entrepreneurs’ self-assessment was rated at 3 out of 7 points, considering that competitors work better.

Prudential sobriety also characterizes Latvian entrepreneurs when it comes to taking risks, introducing new ideas and products proactively thus attempting to beat their competitors. We cannot speak of high competitiveness at such orientation of a strategy, so it would be recommended for Latvian companies to reconsider that it would be worth taking a little more risk and be more aggressive in competitors-oriented activities to improve the company’s position in either domestic or foreign markets.

Rooted in farmsteads, Latvian entrepreneurs are conspicuously passive in using the available contacts and communication networks, which is not only the most effective but also the least expensive ways to attract the necessary external resources for competitiveness. Latvian entrepreneurs derive information on business processes mainly from the Internet and the business press, virtually ignoring the opportunities they could take advantage of in collaboration with business laboratories, universities, and research institutes, local governments, public and non-governmental organizations engaged in business promotion.

Availability of physical resources, such as information technologies, diverse manufacturing equipment was rated as very good by entrepreneurs (5.7 out of 7 points). Similarly, the lack of financial capital is not a significant obstacle to business competitiveness. Although, on the whole, entrepreneurs appreciated it just at 4.3 points, showing that there is still much to be done by policy makers and financial institutions in this field, yet nearly 50% of the surveyed companies assessed financial capital availability as very good, giving 5 to 7 points.

In the section of the survey on environmental impact, 58% of Latvian entrepreneurs assessed the market of their activity as risky where each decision can be crutial. The bulk of the entrepreneurs also admit that the market should be assessed as ill-disposed because it is hard to survive there. At the same time, nearly a half of the respondents noted that the market has a potential, and business growth opportunities increase there. The entrepreneurs tend to expect growing demand in the goods they produce.

In 2012, 72% of Latvian enterprises were able to work with profit. Over, 50% of Latvian enterprises export at least a part of their goods, inter alia, over 16% export at least a half of the produced goods – this is indicative of positive trends and long-term approach to business. The survey shows that increasing of profit will be the priority for Latvian entrepreneurs also in the future (5.8 out of 7 points). Entrepreneurs hope to increase sales on the Latvian market (5.2 points), as well as to reduce costs (5 points) and to improve quality of their products and services (4.8 points).

Bibliography

Alvarez, S., Busenitz, L. (2001). The entrepreneurship of resource-based theory. Journal of Management, 27, pp. 755–775.

Baltrušaityte-Axelson, J.,Sauka, A.,Welter, AF. (2008). Nascent Entrepreneurship in Latvia. Evidence from the Panel Study of Entrepreneurial Dynamics 1st wave. Riga: Stockholm School of Economics in Riga.

Baker, W., Sinkula, J. (2009). 'The complementary effects of market orientation and entrepreneurial orientation on profitability in small businesses', Journal of Small Business Management, 47, pp. 443–464.

Bantel, K. and S. Jackson (1989). 'Top management and innovation in banking: does the composition of the top management team make a difference? Strategic Management Journal, 10, pp. 107–124.

Becchetti, L., Trovato, G. (2002). The determinants of growth for small and medium sized firms. The role of the availability of external finance. Small business Economics, 19, pp. 291–306.

Bougheas, S. (2004). Internal vs external financing of R&D. Small Business Economics 22, pp. 11–17.

Covin, J., Slevin, D. (1989). Strategic management of small firms in hostile and benign environments. Strategic Management Journal, 10, pp. 75–87.

Davidsson, P. (2006). Nascent entrepreneurship: empirical studies and developments. Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship, 2, pp. 1–76.

Dess, G., Beard, D (1984). Dimensions of organizational task environments, Administrative Science Quarterly, 29, pp. 52–73.

Gilley, K., Rasheed, M. (2000). Making more by doing less: an analysis of outsourcing and its effect in firm performance. Journal of Management, 26, pp. 763–790.

Gimeno, J., Folta, T., Cooper, A., Woo, C. (1997). Survival of the fittest? Entrepreneurial human capital and the persistence of underperforming firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42, pp. 750–783.

Greve, A., Salaff, J. (2003). Social networks and entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Fall

Hambrick, D., Mason, P. (1984). Upper echelons: the organization as a reflection of its top managers. Academy of Management Review, 9, pp. 193–207.

Hamermesh, R., Marshall, G., Pirmohamed, T. (2002). Note on business model analysis

for the entrepreneur, 20, 2011, from Harvard Born Globals 38/50 Business

Review:

http://hbr.org/product/note-on-business-model-analysis-for-the-entreprene/an/802048-PDF-

ENG

Helfat, C. (1997). Know-how and asset complementarity and dynamic capability accumulation: the case of R&D. Strategic Management Journal, 18, pp. 339–360.

Hitt, M., Bierman, L., Shimizu, K., Kochhar, R. (2001). Direct and moderating effects of human capital on strategy and performance in professional service firms: a resource based perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 44, pp. 13–28.

Hoang, H. and Antoncic, B. (2003). Network-based research in entrepreneurship. A critical review. Journal of Business Venturing 18, pp. 165–187.

Hughes, M., and Morgan, R. (2007). Deconstructing the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and business performance at the embryonic stage of firm growth. Industrial Marketing Management, 36, pp. 651–661.

Ibeh, K. (2003). Toward a contingency framework of export entrepreneurship: conceptualisations and empirical evidence. Small Business Economics ,20, pp. 49–68.

King, A. and Tucci, C. (2002). Incumbent entry into new market niches: the role of experience and managerial choice in the creation of dynamic capabilities. Management Science, 48, pp. 171–186.

Knight, G., and Cavusgil, S. (2005). A taxonomy of born global firms, Management International Review, 45(3), pp. 15–35.

Kreiser, P., Marino, M., Weaver, K. (2002). Assessing the psychometric properties of the entrepreneurial orientation scale: A multi-country analysis. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Summer, pp. 71–94.

Malecki, E. and Veldhoen, N. (1993). Network activities, information and competitiveness in small firms, Geografiska Annaler. Series B, Human Geography, 75,(3), pp. 131–147.

Man, T.,Lau,T., Chan, K. (2002). The competitiveness of small and medium enterprises. A conceptualization with focus on entrepreneurial competencies. Journal of Business Venturing, 17, pp. 123–142.

McKelvie, A., Davidsson, P. (2009). From resource base to dynamic capabilities: an investigation of new firms. British Journal of Management, 20, pp. 63–80.

Miller, D. (1983). The correlates of entrepreneurship in three types of firms. Management Science, 29, pp. 770–791.

Miller, D., Friesen, P. (1982). Innovation in conservative and entrepreneurial firms: Two models of strategic momentum. Strategic Management Journal, 3, pp. 1–25.

Moreno, A., Casillas, J. (2008). Entrepreneurial orientation and growth of SMEs: A causal model. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, May, pp. 507–528.

Mudambi, R., Zahra, S. (2007). The survival of international new ventures. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(2), pp. 333–352.

Pissarides, F. (1999). Is lack of funds the main obstacle to growth? EBRD's experience with small- and medium- sized businesses in Central and Eastern Europe, Journal of Business Venturing, 14, pp. 519–539.

Porter, M. (1990). The Competitive Advantage of Nations. New York: Free Press.

Rauch, A., Frese, M., Utsch, A. (2005). Effects of human capital and long-term human resources development and utilization on employment growth of small-scale businesses: a causal analysis. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29, pp. 681–693.

Rauch, A., Wiklund, J., Lumpkin, T., Frese, M. (2009). Entrepreneurial orientation and business performance: An assessment of past research and suggestions for the future. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, May, pp. 761–787.

Robson, P., Benett, R. (2000). SME growth: The relationship with business advice and external collaboration, Small Business Economics, 15, pp. 193–208.

Roper, S. (1998). Entrepreneurial characteristics, strategic choice and small business performance. Small Business Economics, 11, pp. 11–24.

Sauka, A. (2011, forthcoming). Latvian Hidden Champions. In H. Simon (Ed.) Hidden Champions from Central and Eastern Europe in Dynamically Changing Environments. Emerald.

Sauka, A. (2008). Productive, Unproductive and Destructive Entrepreneurship: A Theoretical and Empirical Exploration. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang GmbH.

Sauka, A. and Putniņš, T. (2011). SSE Riga "Shadow Economy Index" for the Baltic countries. Riga, Latvia: Stockholm School of Economics in Riga. http://www.sseriga.edu.lv/hadow-economy-index

Sauka, A. and Welter, F. (2011). Mentalities and Mindsets – The Difficulties of Entrepreneurship Policies in the Latvian Context. In F. Welter and D. Smallbone (Eds.)

Handbook of Research on Entrepreneurship Policies in Central and Eastern Europe. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Sauka, A., Welter, F. (2008). Taking Advantage of Transition: The Case of Safety Ltd. in Latvia. In Aidis, R.; Welter, F. (Eds.) 'The cutting edge: innovation and entrepreneurship in new Europe'. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar

Short, J., J. Broberg, C. Cogliser and K. Brigham (2009). Construct validation using computer- aided text analysis (CATA): An illustration using entrepreneurial orientation. Organizational Research Methods: doi 10.1177/1094428109335949

Simon, H. (2009). Hidden Champions of the 21st Century. Success Strategies of Unknown World Market Leaders. New York: Springer

Subramaniam, M., Youndt, M. (2005). 'The influence of intellectual capabilities on the types of innovative capabilities. Academy of Management Journal, 48, pp. 450–463.

Zahra, S., Covin, J. (1993). Business strategy, technology policy and firm performance. Strategic Management Journal, 14, 451–478.

Wright, P., Perris, S., Hiller, J., Kroll, M. (1995). Competitiveness through management of diversity: effects on stock price valuation. Academy of Management Journal, 38, (1), pp. 272–287.