|

|

|

|

|

|

| The twenty-first century is characterized by mobility, ever-increasing flow of information and cooperation among countries in the fields of economics, culture and education. Under these conditions pluriculturality and plurilingualism are attaining new meanings. Building cultural awareness is an extremely significant issue in higher education nowadays as prospective managers will have to contact representatives of different cultures. The study was conducted from May 2009 to April 2011 in the fourth largest tertiary education institution of Latvia providing also higher education in tourism business. The purpose of the study is to analyse the prospective managers’ cultural awareness attained in the studies and its compliance with the requirements of the modern business culture. The sample consisted of 322 tourism students, 192 tourism employers and 144 graduates. The findings of the study show the role of intercultural competence to succeed in tourism business. Suggestions on how to promote prospective managers’ cultural awareness in the studies are elaborated. |

|

Key words: culture, pluriculturality, cultural awareness, business culture, development |

The twenty-first century is characterized by mobility, ever-increasing flow of information and cooperation between countries in the fields of economics, culture and education. Nowadays such ‘terms like plurilingualism, pluriculturality and globalisation are attaining new meanings, ranging from extreme positive humane connotations, to extreme denial and seclusion within one’s local boundaries’ (Babamova et al 2004:59). It is not enough anymore to master only one foreign language and be aware of cultural peculiarities of the target nation. The multicultural context in which the prospective tourism managers will have to work requires the necessity of plurilingual and pluricultural competences, which means cultural awareness in a wider sense.

Plurilingual and pluricultural communication cover an extremely wide area. It means thinking globally, understanding the significance of languages in education, including research-based academic studies and professional studies, as well as diminishing obstacles to pluricultural communication (Pécheur 2001).

Latvia has always been a multicultural and multilingual country. According to the data of the Office of Citizenship and Migration Affairs, in July 2011, 156 nationalities and ethnic groups lived in Latvia. The largest nationalities included Latvians (1,323,713 people), Russians (606,972), Byelorussians (78,052), Ukrainians (54,398) and Poles (50,960) (Latvijas iedzīvotāju sadalījums pēc nacionālā sastāva un valstiskās piederības 2011). The 2000 Population Census data show that of 2.38 million inhabitants, Latvian is the mother tongue for 1.38 million people and Russian for 892,000 people. Excluding native speakers,nearly 496,000 people admitted having a good command of Latvian and1.04 million a good command of Russian.Other popular languages were English (339,949 speakers), German (179,446), Byelorussian (17,215) and French (9752) (Results of the 2000 Population and Housing Census in Latvia 2002:147).

Plurilingualism and pluriculturality are significant in any sphere connected with people, and, as we do not live in an isolated world, we cannot restrict ourselves from globalization; and employees have to face it on a daily basis at work. As School of Business Administration Turība educates future managers in different fields, including tourism business, special attention is being paid to the promotion of the development of students’ intercultural competence and cultural awareness for their work in the modern business environment.

The paper analyses the issues connected with the prospective tourism managers’ cultural awareness attained in the studies and its compliance with the requirements of the modern business culture.

Theoretical Framework of the study is based on understanding of pluriculturality and plurilingualism in the modern business world and their implementation in the studies.

The core of the notion of culture is formed by three essential features: 1) culture as a social reality; 2) culture as a system of values; 3) culture as people’s activity. It is the basis for the existence of a society, a form of creating, preserving and passing of social information (Vedins 2008). As culture is the major determinant of people’s thoughts and behaviour (Stier 2006; Van Oord 2008), it is the basis of people’s socializationand the basis for the development of people and society (Vedins 2008). ‘Culture comprises anything and everything constructed and influenced by man and leavens through every layer and domain of society’ (Stier 2004:6). All the elements of culture (verbal and written language, non-verbal language, symbols, meanings, traditions, habits, customs, norms, rules, ethic, collective views on the phenomena, etc.) taken together make up a prism through which employees communicate, interpret and experience the world (Stier 2004).

Culture is a complicated, manifold phenomenon. It is not genetically inherited, but is acquired in the process of socialization in a definite cultural environment. When interpreting culture, the context is always very important. Culture can be explained from the point of view of philosophy, sociology, politics, business and other fields (Dubkēvičs 2009).

Bodley (2011) distinguishes the following approaches to culture: topical, historical, behavioural, normative, functional, mental, structural and symbolic. The applied approach to this study incorporates topical and functional approach to culture. The topical approach supports the point of view that culture includes everything in the list of topics or categories, e.g., social organization, economics, etc., whereas the functional approach regards culture as a way how humans solve problems of adapting to the environment or living together.

Culture denotes different activities, including communication, which contribute to socialization and raising of cultural awareness. The central feature of communication is social interaction as people acquire cultural values and interactive rules of communication by interacting with others. ‘Language awareness and cultural awareness very often interact with each other in the sense that activities focussing on one of these areas very often involve the other as well’ (Penz 2001:93). In turn, interaction, socialization and experience are characteristic exposures of learning.

Business cultureis a set of core values, opinions, unofficial agreements and norms accepted by the society or organization (Daft 2011). Corporate business culture is a set of mental values and the way of doing business deals (Летуновский 2011). National business culture comprises those values created in the national environment which influence business processes in the country. Business culture is determined not only by the correspondence of the management quality level to international requirements, but also by traditional mental values of the country that have stood the test of time. Globalization creates new business culture. However, globalization not only levels the rules of the game for every country, but also causes threats. Therefore, countries continue protecting their frontiers, their national markets from the consequences of globalization (Kotler et al 2010). Thus, globalization promotes strivings to protect the values characterizing the country’s ethnos. In some countries these strivings are more expressed than in others. In Latvia the Law on the Official Language (Valsts valodas likums 1999) is in force which declares Latvian as the official language of the country and protects language as a cultural value.

Business culture has two interrelated and at the same time relatively independent parts: a relatively constant part or traditional culture and a changeable part or the new international culture. International trade relations, their intensity, migration processes and other external and internal factors connected with globalization influence the changeable part of the culture.

The basis of business is a deal or exchange. At least two parties have to be involved in a business deal and every party must possess something valuable for the other one. Both parties, i.e., demand and supply, are united by communication whose value is determined by business culture which, in fact, is the main component of the product value. Success of business deals, including tourism, nowadays depends on the business culture, not on other values of the product (Nakamoto 2008).

Business culture is gradually changing and it is determined by the market as the values are changing. Orientation towards a client, loyalty, creativity, self-directedness, tolerance, and decentralization are just some of the notions that describe contemporary business culture (Kotler et al 2010). To summarize, contemporary business culture is characterized by an ability to adapt to cultural differences and tolerance, which create an added value to the business deal, thus, promoting cooperation. It marks a shift from cooperation with the client (Prahalad and Ramaswamy 2004) to enhancing social responsibility considering the needs of the society (Kotler et al 2010).

Therefore, to succeed both in one’s professional and personal life, it is essential to learn how to communicate with people from other cultures (Lee 2006) which means that in the studies special attention has to be paid to raising students’ cultural awareness.

Cultural awareness‘is the foundation of communication and it involves the ability of standing back from ourselves and becoming aware of our cultural values, beliefs and perceptions’ (Quappe and Cantatore 2007:1). Developing cultural awareness means understanding oneself, knowing one’s roots, knowing to what culture one belongs, as well as recognizing the fact that there are ‘cultural differences in the world of international cooperation’ (Merk 2003:2). In turn, awareness of other cultures enables people to look at phenomena from a wider perspective, thus, contributing to understanding of their own culture and the values of their national culture. In such a way people not only are aware of different national cultures, but they also raise their self-awareness (Etus 2008). Raising cultural awareness means that people are able to perceive positive and negative aspects of cultural differences.

One of the differences is the way of communication which differs in different parts of the world. For example, ‘Eurocentric communication style values personal thoughts, feelings and actions in communication. Individuals are encouraged to express their ideas precisely, explicitly and directly, whereas Asiacentric communication style pays attention to harmonious relationships in which silence matters (Lu and Hsu 2008:76). In turn, Americans are more open and gesticulate more. As prospective tourism managers will work in a different cultural environment and cooperate with counterparts from different cultures, students have to be exposed to different communication styles in the studies.

‘The integration of social interaction with peers of the target language and culture’ (Penz 2001:94) contributes both to language and culture learning. In order to form mutual understanding among different groups and among the group members themselves it is crucial to possess a high level of intercultural competence which might be developed applying intercultural approach in the studies.

Intercultural approach is regarded as a student-centered approach because it addresses the issues of dealing with otherness and difference. It integrates the students’ own socio-cultural context (structures, traditions, value systems, stereotypes) into learning (Neuner 2001). This coincides with pluriculturality as pluricultural communication means willingness to accept otherness, being able to reflect on it and maintain a dialogue (Katnić-Bakarsić 2001). In fact, we can speak here of transcultural competence whose aim is to provide students with the confidence as a foreign insider in another culture (Schechtman and Koser 2008), so, that students facing the situation in reality could make a more successful communication.

Education and culture are related. Education contributes to raising cultural awareness by forming a broad and advanced base for knowledge, enabling students’ personal and professional development, preparing for life in a democratic society (Battaini-Dragoni 2010) and operating in the multicultural business world.

Purpose of the Research

The purpose of the study is to analyze the enhancement of prospective tourism managers’ cultural awareness attained in the studies and its compliance with the requirements of the modern business culture.

Research Questions

Research Framework

The analysis of cultural awareness is made by applying the approach of the revised Bloom’s (Bloom, 1956; Krathwohl et al 1973) taxonomy of the cognitive domain (Anderson and Krathwohl, 2001), which distinguishes the following phases: remembering, understanding, applying, analyzing, evaluating and creating. The new category – creating, which includes an ability of being able to create new knowledge within the domain, is the highest level to be achieved (Atherton 2011). The revised levels have been selected as the criteria for evaluation of students’ cultural awareness. Remembering means that students are able to recall the information, understanding includes explaining and describing concepts, applying is using the information in a new way or interpreting it, analyzing involves differentiation between different components of relationships demonstrating the ability to compare and contrast. Both evaluation and creating are significant and they include analysis as a foundational process. However, creating requires rearranging the parts in a new, original way, whereas evaluating requires a comparison to a standard with a judgment as to the quality (Huitt 2011). Thus, creating is the highest level to be attained.

The study consisted of the following stages:

Research Methods

Mixed methods of the research (quantitative and qualitative) were selected for the study to increase its reliability and validity (Hunter and Brewer 2003; Kelle and Erzberger 2004). The following research methods were applied: an analysis of theoretical literature and sources, empirical methods – data collection (surveys containing structured and open questions), data processing and analysis methods (primary and secondary quantitative data analysis by applying SPSS 16.0 software – frequencies, means, Oneway Anova test, Cronbach’s Alpha Reliability and Validity test (Griffin 2009) and discourse analysis (Lynch 2007) for the analysis of qualitative data).

Sample

The sample of the study was composed based on the approach of Raščevska and Kristapsone (2000) and Geske and Grīnfelds (2006).

Convenience sample was composed from 262 students studying at the Faculty of International Tourism of Turiba University: 93 first year, 80 second year, 56 third year students, 33 foreign students. 168 students (64.1%) had worked in hotel business, 69 students (26.3%) in catering industry and others in travel agencies, tourism information centres.

Intentional sample of 192 tourism employers of the enterprises, in which the students had undergone internship, were questioned. Intentional sample was formed because it was important to compare the findings of the students’ and employers’ surveys. The employers were addressed personally by e-mail and the response rate was 86%. 84 (43.8%) were top level managers, 57 (29.7%) were medium level managers, 51 (26.6%) others.

Intentional sample of 61 fourth year tourism students who had undergone all the training envisaged by the curriculum was surveyed. 33 respondents (54.1%) had undergone internship only in Latvia, whereas 8 respondents had not done internship in Latvia at all.

Simple random sample of 144 respondents was formed for graduates’ survey. Majority of respondents work in a tourism related enterprise (76 respondents or 52.8%). Most of them are involved in restaurant business (18 respondents or 23.7%) and in hotel business (15 respondents or 19.7%). 21 respondents (27.6%) represented medium-size tourism establishments and 22 respondents (28.9%) – large tourism establishments.

The findings of the students’ and graduates’ self-evaluation of their knowledge, skills and abilities characterizing cultural awareness, and the findings of the employers’ survey evaluating the students’ knowledge, skills and abilities characterizing their cultural awareness indicate their quite high level. The findings indicate similarity in the students’ and employers’ opinion regarding evaluation of the students’ knowledge, skills and abilities. Both surveys show relatively high means: from 3.6221 to 5.6870 (max=6) in the students’ survey and from 3.5208 to 5.7760 (max=6) in the employers’ survey. The average means of the students’ survey is 4.7784 and in the employers’ survey – 4.9089. Another similarity is found in the top five most significant issues demonstrated in both surveys. The highest scores are given to the Latvian language skills, abilities to communicate with colleagues and an ability to work in a multicultural team followed by the abilities to communicate with clients and knowledge of communication psychology. The graduates’ survey shows slight differences from the students’ and employers’ surveys. In the top positions the graduates have abilities to communicate with clients and colleagues, to work in a multicultural team, as well as organizational skills and creativity. The average mean for the graduates’ survey is 4.5756 (max=6) which is similar to the students’ and employers’ surveys. The means are ranging from 3.1458 to 5.2361 which is slightly lower than in the students’ and employers’ surveys (see Table 1).

| Table 1. Means of evaluation of graduates’ and students’ knowledge, skills and abilities (max=6) | ||||

|

Knowledge, skills, abilities |

Code |

Evaluation of students’ knowledge, skills, abilities |

Graduates’ knowledge, skills, abilities |

|

|

Students’ survey |

Employers’ survey |

Graduates’ survey |

||

|

Understanding the work of tourism business |

1 |

4.8282 |

4.9635 |

4.6250 |

|

Knowledge of communication psychology |

2 |

5.1069 |

5.1979 |

4.8681 |

|

Knowledge of Latvia and world tourism geography and globalization |

3 |

4.5038 |

4.5573 |

4.4097 |

|

Knowledge of travel organization and management |

4 |

3.9618 |

4.1510 |

4.1736 |

|

Knowledge of marketing |

5 |

4.0687 |

4.3958 |

4.5694 |

|

Latvian language skills |

6 |

5.6870 |

5.7760 |

not applicable |

|

English language skills |

7 |

4.9542 |

5.1146 |

4.8472 |

|

Russian language skills |

8 |

4.8321 |

4.9688 |

4.4653 |

|

German/French language skills |

9 |

3.6221 |

3.5208 |

3.1458 |

|

Abilities to communicate with clients |

10 |

5.2863 |

5.3229 |

5.2361 |

|

Abilities to communicate with colleagues |

11 |

5.4618 |

5.5729 |

5.1875 |

|

Organizational skills |

12 |

4.7252 |

5.0208 |

4.9444 |

|

Ability to work in a multicultural team |

13 |

5.2824 |

5.4688 |

5.1597 |

|

Ability to apply theoretical knowledge into practice |

14 |

4.9313 |

5.0938 |

4.8333 |

|

Strategic approach to entrepreneurship |

15 |

4.4313 |

4.5208 |

4.6597 |

|

Creativity |

16 |

4.7710 |

4.8958 |

4.9306 |

|

Problem-solving skills |

17 |

not applicable |

not applicable |

4.9236 |

|

Presentation skills |

18 |

not applicable |

not applicable |

4.8264 |

The differences might be explained by the fact that in the graduates’ survey the item regarding the Latvian language skills was excluded since the Law of State (Latvian) Language (Valsts valodas likums 1999) requires a definite level of the state language skills from graduates. There were included two other items: problem-solving skills and presentation skills that are significant attributes for work in tourism business. The similarity between all three surveys is found in the issue regarding the third foreign language (German/French) skills which has a low evaluation by the students (mean=3.6221), employers (mean=3.5208) and graduates (mean=3.1458). However, considering the incoming tourism tendencies in Latvia these skills have to be enhanced.

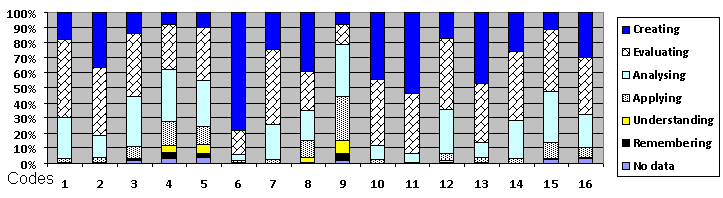

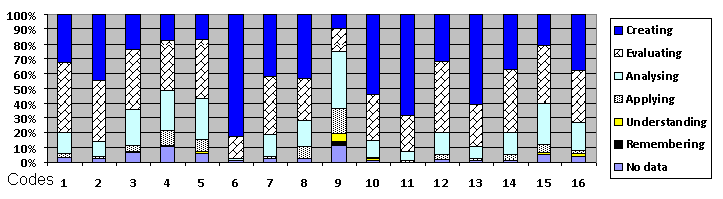

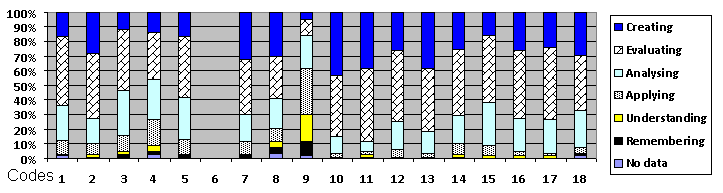

The applied approach of the revised Bloom’s taxonomy of the cognitive domain (Anderson and Karthwol 2001) shows that most of the results fall under the categories of analyzing, evaluating and creating, which demonstrates the students' and graduates’ ability to apply the acquired knowledge and developed skills in practice in a multicultural working environment (see Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3) (refer for codes to Table 1).

|

| Figure 1: Students’ self-evaluation of knowledge, skills and abilities. |

|

| Figure 2: Evaluation of students’ knowledge, skills and abilities by employers. |

|

| Figure 3: Graduates’ self-evaluation of knowledge, skills and abilities. |

The students’ self-evaluation indicates that the highest score is given to the Latvian language skills where 205 students (from 262) admit that these skills are in the phase of creating which is natural since Latvian is the mother tongue for most of the students. Abilities to communicate with colleagues and clients also fall under the highest categories. 142 students admit communication abilities with colleagues in the phase of creating and 104 students – in the phase of evaluating. 117 students find their communication abilities with clients in the phase of creating and 113 students – in the phase of evaluating. Communication abilities are developed in a range of courses: foreign language courses, communication psychology, personnel management, management, history and culture courses, etc.

The employers’ survey shows similar results to the students’ survey. 184 employers (from 192) find students’ knowledge of communication psychology as very good – 86 employers think that it is in the phase of creating, 79 that it is in the phase of evaluating and 19 employers find it in the phase of analyzing. The employers also highly evaluate the students’ language skills and communication skills. It has to be emphasized that employers highly evaluate students’ ability to work in a multicultural team – 117 employers find this ability in the phase of creating and 55 employers find it on the phase of evaluating. However, a low evaluation is given to the students’ creativity. Although 74 employers find it in the phase of creating and 66 employers in the phase of evaluating, these scores are comparatively lower than for the other skills and abilities. This means that creativity has to be enhanced in the studies. Creativity may be enhanced by doing project work and group work, participating in discussions, playing role plays, doing simulations and case studies.

Compared to the students’ and employers’ surveys, the graduates’ survey shows a higher proportion of scores corresponding to the phase of evaluating than to the phase of creating. For example, 73 graduates (from 144) evaluate their abilities to communicate with colleagues corresponding to the phase of evaluating and 55 graduates evaluate them as being in the phase of creating. A more vividly expressed difference is regarding the graduates’ self-evaluation of understanding the work of tourism business where 68 graduates admit it corresponding to the phase of evaluating and only 28 graduates find it in the phase of creating.

Cronbach’s Alpha Reliability Statistics and Item-Total Statistics tests show a high data reliability for the students’ survey (α=0.804), employers’ survey (α=0.882) and the graduates’ survey (α=0.876). In the graduates’ survey Corrected Item-Total Correlation coefficient shows that the Russian language skills have a low value (below 0.2) which means that this item has to be excluded from further data analysis. Excluding the item from further analysis ensures an increase in data reliability (α=0.897).

Oneway Anova test reveals differences in the findings of the three questionnaires. Analysing findings by the respondents’ group in 9 issues from 16 there were discovered significant differences (p≤0.05) and, similarly, analyzing findings by the respondents’ post in 9 issues from 16 there were discovered significant differences (p≤0.05) (see Table 2).

The Latvian language skills were excluded from comparison since they were not evaluated in the graduates’ survey. The Russian language skills were excluded from comparison because of the low reliability coefficient in Cronbach’s Alpha test. Problem-solving skills and presentation skills were excluded from comparison because they were not analyzed in the students’ and employers’ surveys. The findings indicate that the acquired knowledge, and developed skills and abilities are influenced by the respondents’ group which implies experience, as there were three groups under investigation – students, graduates and employers. Similarly, they are affected by the respondents’ post in the organization which ranged from the lower posts (maid, bartender, waiter, waitress) to more advanced jobs (travel consultant, receptionist, housekeeper, travel consultant, manager) and to company owners. Thus, it is evident that again experience differentiates the respondents’ knowledge, skills and abilities. Students’ experience might be developed in the studies during lectures, seminars, workshops. It might be promoted in discussions, meetings, mutual interaction, cooperation and collaboration among peers and between students and professors. Another important factor enhancing the development of students’ experience is internship in the industry.

| Table 2. Synopsis of Oneway Anova test regarding students’ and graduates’ knowledge, skills and abilities | |||||

|

Knowledge, skills, abilities |

Code |

Evaluation done by students, graduates and employers |

|||

|

Analysis by respondents’ groups |

Analysis by respondents’ post |

||||

|

F |

Sig. |

F |

Sig. |

||

|

Understanding the work of tourism business |

1 |

4.654 |

0.010 |

1.774 |

0.039 |

|

Knowledge of communication psychology |

2 |

4.579 |

0.011 |

2.219 |

0.006 |

|

Knowledge of Latvia and world tourism geography and globalization |

3 |

0.588 |

0.556 |

1.813 |

0.034 |

|

Knowledge of travel organization and management |

4 |

1.366 |

0.256 |

2.034 |

0.014 |

|

Knowledge of marketing |

5 |

7.358 |

0.001 |

3.499 |

0.000 |

|

Latvian language skills |

6 |

not applicable |

|||

|

English language skills |

7 |

3.082 |

0.047 |

1.488 |

0.110 |

|

Russian language skills |

8 |

not applicable |

|||

|

German/French language skills |

9 |

5.289 |

0.005 |

1.599 |

0.075 |

|

Abilities to communicate with clients |

10 |

0.398 |

0.672 |

1.782 |

0.038 |

|

Abilities to communicate with colleagues |

11 |

10.574 |

0.000 |

2.847 |

0.000 |

|

Organizational skills |

12 |

6.171 |

0.002 |

1.306 |

0.198 |

|

Ability to work in a multicultural team |

13 |

5.783 |

0.003 |

2.249 |

0.006 |

|

Ability to apply theoretical knowledge into practice |

14 |

3.511 |

0.030 |

1.948 |

0.020 |

|

Strategic approach to entrepreneurship |

15 |

1.866 |

0.156 |

0.574 |

0.886 |

|

Creativity |

16 |

0.972 |

0.379 |

1.005 |

0.446 |

The conducted in-depth survey of the fourth year tourism students applying an open questionnaire supported the findings of the quantitative study. The respondents have emphasized that the language skills, namely - English, Russian and German, are crucial for intercultural communication. A significant problem in communication with colleagues mentioned was the lack of sufficient English language skills (16 respondents or 26.3%). The communication was further complicated by the lack of the local state language skills which had been mentioned by several students who had undergone internship abroad. Communication problems with colleagues also arose due to differences in temperament, mentality and global outlook (12 respondents or 19.7%).The respondents noted the biggest discrepancy while working with the Greek colleagues indicating that ‘Greeks perceive everything very emotionally’ (Student 43), as well as ‘they are impulsive, emotional’ (Student 35), which is in contrast with the Latvian temperament and traditions.

The students also experienced problems connected with understanding of different cultures. It is evident from the respondents’ answers that the students, undergoing internship abroad, encountered more untraditional situations and quaint behaviour than those working in Latvia. Cultural differences were connected with the Latvian students’ behaviour abroad, namely, their colleagues were surprised about the Latvian eating habits. The students also encountered problems connected with eating and drinking habits of their guests. The survey showed that more attention should be paid to introducing students not only to the European cultures, but also to the Arab and Asian cultures, as the students admitted that they had had the largest difficulties when meeting the clients from the Oriental countries. This could be done by selecting appropriate texts, case studies and promoting discussions in the group.

The findings of the study indicate that, in general, the students – future managers, of tourism business are aware of the meaning of culture and its importance in business nowadays, as well as the students’ and graduates’ cultural awareness complies with the requirements of the modern business world. However, the study points to several drawbacks, i.e., further challenges for development. Cultural differences significantly influence interaction, communication, negotiations and their results. Stereotypes or naivety about the culture of some country or nation frequently cause serious problems. Some cultural differences are generally known but, as the survey shows, their nuances may expose in quite an unexpected aspect and moment.

In order to promote future tourism managers’ success in business and to make the process more targeted, Turiba University has worked out guidelines for the improvement of the study process so that it would enhance the development of students’ attitude and behaviour. The study process has to develop:

To develop intercultural communication skills and enhance students’ cultural awareness it is necessary to effectively use internship periods, including internship abroad, as well as student exchange programme Erasmus, and envisage conducting research connected with the themes that strengthen the culture of thinking and behaviour. Such an approach would further students’ self-criticism and develop practical cognition required in management. It would promote students’ understanding of the necessity to be aware of the values and peculiarities of the other side and respect them. It would make the students aware that in business it is worth concentrating on similarities, not differences, and managers have to learn the art of compromise, i.e., in communication with representatives of other cultures choose such a style that would create the win-win situation, as the aim of communication is to reach an agreement convenient for both sides.

Higher education institutions face a complicated task, as one of their missions is to educate the intellectuals (intelligentsia) of their country. Every higher education institution can choose its own model of business culture. The authors consider that the dominant tasks in creating business culture in a higher education institution have to be connected with the development of students’ knowledge (an ability to constantly and independently upgrade it), critical creativity (an ability to analyse the achieved and to search new ideas) and tolerance (an ability to be tolerant in looking for associates and listening in others).

Business culture promotes partnership, trust and, consequently, a successful communication in business. The lack of competence in business culture of the other region or country is often a cause of failures in international business, as relationship/attitudes acceptable in one culture may be unacceptable in another. Differences may exist even between comparatively geographically closely situated countries.

The study indicates that the students’ and graduates’ knowledge and skills of business culture are contemporary enough. However, it refers only to general or international, global processes. The business culture of such a small country as Latvia has to be very versatile and flexible: entrepreneurs must be aware of the national culture of certain countries and regions of the world – their values, traditions and ways of communication. Latvian entrepreneurs have to be well informed on the events in the potential business partner’s country and must be able to adapt to their partner’s business culture not losing their own identity.

Cultural awareness means the development of views which is acquired life long. Business culture cannot be taught at a university. University must provide tools for enhancing students’ cultural awareness. On the basis lie characteristics of the business culture of other countries, comprehension of traditions of other regions, verbal and non-verbal communication culture. In order to enhance cultural awareness, it is essential to understand oneself, one’s own culture. Students should be taught how to conduct self-analysis and self-evaluation in this respect.

For the enhancement of prospective tourism managers’ cultural awareness, tertiary level tourism students could acquire the course “Business culture and communication” in which the successes and losses of business traditions of the world-scale tourism establishments would be analyzed.

When organizing the study process, including acquiring the versatile aspects of business culture, it is necessary to consider the specifics of the current Generation Y (often called as Generation Me) (Van den Bergh and Behrer 2011) that has been accustomed to “getting most out of their lives” (ibid 5) and who will be the future collaboration partners of the present day students. The role of cultural awareness will continue increasing in the future.

Anderson, L.W., Krathwohl, D.R. (eds.) (2001). A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom's Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. New York: Longman, 352 p.

Atherton, J.S. (2011). Learning and Teaching; Bloom's taxonomy. [28.04.2011.]. Retrieved from http://www.learningandteaching.info/learning/bloomtax.htm

Babamova, E., Grosman, M., Licari et al. (2004). Cultural awareness in curricula and learning materials. In Cultural mediation in language learning and teaching, Kapfemberg: Council of Europe Publishing, pp.59-100.

Battaini-Dragoni, G. (2010). Round table speech at Conference of Ministers responsible for Culture Baku, 2-3 December 2008. “Intercultural dialogue as a basis for peace and sustainable development in Europe and its neighbouring regions”. Council of Europe, pp.93-97.

Bloom, B.S. (ed.). (1956). Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, the classification of educational goals – Handbook I: The Cognitive Domain. New York: Longman, 207 p.

Bodley, J.H. (2011). Cultural Anthropology: Tribes, States, and the Global Systems. Plymouth: Alta-Mira Press, 632 p.

Daft, R.L. (2011). Management. Australia: South-Western Cengage Publishing, 682 p.

Dubkēvičs, L. (2009). Organizācijas kultūra. Riga: Jumava, 182 lpp.

Etus, Ö. (2008). Fostering inter-cultural understanding in pre-service language teacher education programmes. Whose culture(s)? Coudenys, W. (ed.). Proceedings of the Second Annual Conference of the University Network of European Capitals of Culture, Liverpool, 16-17 October, 2008, pp.158-174.

Geske, A., Grīnfelds, A. (2006). Izglītības pētniecība. Rīga: LU Akadēmiskais apgāds, 261 lpp.

Griffin, B.W. (2009). Cronbach’s Alpha (measure of internal consistency). EDUR 9131 Advanced Educational Research. [15.08.2011.]. Retrieved from http://www.bwgriffin.com/gsu/courses/edur9131/content/cronbach/cronbachs_alpha_spss.htm

Huitt, W. (2011). Bloom et al.'s taxonomy of the cognitive domain. Educational Psychology Interactive. Valdosta, GA: Valdosta State University. [28.04.2011.]. Retrieved from http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/topics/cognition/bloom.html

Hunter, A., Brewer, J. (2003). Multimethod Research in Sociology. In Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social & Behavioral Research. Tashakkori, A., Teddlie, C.B. (eds.) London, New Delhi: Sage Publications, International Educational & Professional Publisher, Thousand Oaks, pp.577-593.

Katnić-Bakarsić, M. (2001). Overcoming obstacles to plurilingualism. In Living together in the Europe in the 21st century: the challenge of plurilingual and multicultural communication and dialogue. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing, pp.41-44.

Kelle, U., Erzberger, C. (2004). Qualitative and Quantitative methods: Not in Opposition. In Companion to Qualitative Research. Flick, U., vonKardoff, E., Steinke, I.A. (eds.). London: Sage Publications, pp.172-177.

Kotler, P., Kartajaya, H., Setiawan, I. (2010). Marketing 3.0. From Products to Customers to the Human Spirit. USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 188 p.

Krathwohl, D.R., Bloom, B.S., Masia, B.B. (1973). Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, the Classification of Educational Goals. Handbook II: Affective Domain. New York: David McKay Co., Inc., 196 p.

Latvijasiedzīvotājusadalījumspēcnacionālāsastāvaun valstiskāspiederības. (2011). [16.08.2011.]. Retrieved from http://www.pmlp.gov.lv/lv/statistika/dokuments/2011/2ISVN_Latvija_pec_TTB_VPD.pdf

Lee, P.W. (2006). Bridging cultures: understanding the construction of relational identity in intercultural friendship. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, 35(1), 3-22. DOI: 10.1080/17475740600739156

Lu, Y., Hsu, C.F. (2008). Willingness to communicate in intercultural interactions between Chinese and Americans. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, 37(2), 75-88. DOI:10.1080/17475750802533356

Lynch, M. (2007). Discourse Analysis. In SAGE Handbook of Social Science Methodology. Outhwaite, W., Turner, S.P. (eds.).London: SAGE Publications, pp.499-515.

Merk, V. (2003). Communication across Cultures: from cultural awareness to reconciliation of the dilemmas. FEEM Working Paper No. 78.2003., 20 p.Economic Growth and Innovation in Multicultural Environments (ENGIME). DOI:10.2139/ssrn.464720

Nakamoto, S. (2008). Talk Like a Winner! Huntington Beach, CA: Java Books, 240 p.

Neuner, G. (2001). The intercultural approach in curriculum and textbook development. In Living together in the Europe in the 21st century: the challenge of plurilingual and multicultural communication and dialogue. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing, pp.87-92.

Pécheur, J. (2001). Towards a better understanding of the theme of plurilingual and multicultural communication and dialogue. In Living together in the Europe in the 21st century: the challenge of plurilingual and multicultural communication and dialogue. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing, pp.143-146.

Penz, H. (2001). Exploring otherness, differences and similarity through social interaction. In Living together in the Europe in the 21st century: the challenge of plurilingual and multicultural communication and dialogue. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing, pp.93-100.

Prahalad, C.K., Ramaswamy, V. (2004). The Future of Competition: Co-Creating Unique Value with Customers. Boston: Harward Business Press, 257 p.

Quappe, S., Cantatore, G. (2007). What is Cultural Awareness, anyway? How do I build it? Culturosity.com.[23.04.2011.]. Retrieved fromhttp://www.culturosity.com/articles/whatisculturalawareness.htm

Raščevska, M., Kristapsone, S. (2000). Statistika psiholoģiskajos pētījumos. Rīga: Izglītības soļi, 356 lpp.

Resultsofthe2000 PopulationandHousingCensusinLatvia.(2002).Riga:CentralStatisticalBureauofLatvia.

Schechtman, R.R., Koser, J. (2008). Foreign Languages ND Higher Education: A Pragmatic Approach to Change. The Modern Language Journal, 92(2), 309-312. DOI: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.2007.00719_9.x

Stier, J. (2006). Internationalisation, intercultural communication and intercultural competence. Journal of Intercultural Communication, 11. [23.04.2011.]. Retrieved from http://www.immi.se/intercultural/nr11/stier.pdf

Stier, J. (2004). Intercultural competencies as a means to manage intercultural interactions in social work. Journal of Intercultural Communication, 7. [23.04.2011.]. Retrieved from http://www.immi.se/intercultural/nr7/stier.pdf

Valsts valodas likums(1999). ("LV", 428/433 (1888/1893), 21.12.1999.; Ziņotājs, 1, 13.01.2000.) [in force since 01.09.2000.] [12.08.2011.]. Retrieved from http://www.likumi.lv/doc.php?id=14740

Van den Bergh, J., Behrer, M. (2011). How Cool Brands Stay Hot. Branding to Generation Y. London, Philadelphia, New Delhi: Kogan Page Limited, 254 p.

Van Oord, L. (2008). After culture: Intergroup encounters in education. Journal of Research in International Education, 7(2), 131-147. DOI: 10.1177/1475240908091301

Vedins, I. (2008). Zinātne un patiesība. Rīga: Izdevniecība Avots, 702 lpp.

Летуновский, В.В. (2011). Бизнес-культура и национальные корни. [09.08.2011.]. Retrieved from http://msk.treko.ru/show_article_1077