|

|

|

|

|

|

| Riga is a relatively new tourism destination. And as is the tourism industry expanding, so are the negative effects, such as rising prices, noise and carbon pollution, unplanned building, etc., and so terms of sustainable tourism development must be taken into consideration. Therefore the aim of the paper is to analyze the contribution of cycling tourism to sustainable tourism development in Riga. The research consists of two main parts: analyzing the cycling tourism product and the demand. To analyze the product, a model by Simonsen et al. (1998, p.47) has been implemented in the research. In order to analyze the demand, a survey has been conducted, focusing on questions such as importance of cycling tourism product components (based on the model mentioned above) and their evaluation in Riga, as well as determining tourists’ motivation and perception towards cycling as a sustainable type of tourism. Based on the findings of the study and the problems stated, suggestions for possible future actions and/or studies have been elaborated. The main research conclusions are that basic components of the cycling tourism product of Riga are evaluated lower than the general importance in an urban destination. However, the municipality of Riga realizes the importance of cycling in terms of sustainable development; therefore some actions towards development have been taken. |

|

Key words: cycling tourism, sustainable tourism development |

Riga is the most popular tourist destination in Latvia with 1.1 mlj visitors in 2009, mostly from Russia, Scandinavia and Germany. (Development program of Riga, 2010) In 2010 the most frequent questions asked in Tourist offices were cultural and historical sites (35%), services, such as dining and shopping (22%) and city tours (12%). As for inquiries about cycling tourism opportunities, it has increased 2.3 times, compared to year 2010 and 2011. (Riga TIC, 2011)

As for the cycling tourism, it is considered to be one of the most sustainable types of tourism. (Simonsen et al. 1998) In the developed countries such as Netherlands, Denmark or Germany, cycling is a big part of everyday lives in the local communities. No surprise, that these are the main cycling tourist countries with Netherlands reaching 30%, Denmark 18% and Germany up to 10% of cycling trips (Pucher & Buehler 2008). Since Germany and Scandinavia share a great part in Latvia’s tourism market, their demand in cycling tourism has to be taken into consideration. Therefore this study deals with the following research question: How can cycling tourism contribute to sustainable tourism development in Riga?

In order to answer the research question stated above, post-positivism is chosen as the paradigm of this study. The research is broad rather than specialized and formed more as a learning role than a testing one, stating a problem rather than solving it. Referring to Guba (1990), reality exists, but it is impossible to reach certain truth because of modified objectivism. Therefore the approach of this paper is interpretive, emphasizing meaning and creation of new knowledge that may be a subject to change in the future.

This research consists of two main parts: analyzing the cycling tourism product and the demand. The first part of the paper is concerned with theoretical analysis of what cycling tourism is, what impact cycling commits to an urban destination and how cycling tourism contributes to sustainable tourism development. The second part consists of cycling tourism product and demand analyses. To analyze the product, a model of cycling tourism product in Denmark by Simonsen et al. (1998, p.47) has been implemented in the research, analyzing primary experienced and organizational products, marketing infrastructure and means of distribution. This model was chosen because of the suitability for analysis, since the model embraces all the basic cycling tourism components in an urban destination. In order to analyze the demand, a survey has been conducted, using the purposeful (intentional) sampling applying the grouping method of similar cases (Gekse & Grinfelds 2006). Survey was focusing on young people and responding to questions such as importance of cycling tourism product components (based on the model mentioned above) and their evaluation in Riga, as well as determining tourists’ motivation and perception towards cycling as a sustainable type of tourism. In the survey 142 respondents participated, 100 female and 42 male, age mainly 18-34, mostly students or working people. In order to evaluate the components, Lickert scale was chosen where 1 means the least important/very poor and 5 means the most important/very good. In the end, all the results have been taken into consideration, the main problems stated, and suggestions for possible future actions and/or research elaborated.

Nevertheless, it has to be noted, that this study is focusing only on one city, as well as on one type of respondents (considering age and occupation). This leads this study to some limitations in terms of generalizing demand and destination. Another important factor is that the research of demand holds only quantitative data, so for further or more detailed investigation, qualitative measures should be used.

The relationship between cycling and tourism is quite complex as there are several attempts at defining bicycle tourism and tourists, but the literature is fragmented by the use of different parameters in analyzing it. For example, Lumsdon (1996) defines cycling tourism as a recreational cycling activity, which can be a long-distance trip or just a short excursion. At the same time Ritchie (1998, pp. 568–569) emphasizes the period of time: ‘A person who is away from their home town or country for a period not less than 24 hours or one night, for the purpose of a vacation or holiday, and for whom using a bicycle as a mode of transport during this time away is an integral part of their holiday or vacation.’ Ritchie’s definition basically excludes the same-day travelers or half day excursions, by extending the period of time as the minimum of 24 hours, while in the South Australian Cycle Tourism Strategy 2005-2009 (South Australian Tourism Commission 2005) the length of the cycling is not defined as important, as long as it is done for pleasure, recreation or sport. Then again, Simonsen et al. (1998, p.21) express that ‘a cycling tourist is a person of any nationality, who at some stage or other during his or her holiday uses the bicycle as a mode of transportation, and to whom cycling is an important part of this holiday.’ This definition embraces different types/forms of cycling tourists, which, according to its authors can be graded by their ‘level of commitment to the cycling tourism concept and purpose of cycling holiday, including regular cycling enthusiasts as well as occasional cyclists’. (ibid.) In this case the length of the trip is not important. Finally, Lamont (2009) embraces all of these concerns in his study about cycling tourism definitions, by including both overnight and same-day visitors as cycling tourists, as long as cycling is the main purpose for their journey, whereas Sustrants (1999) divides cycling tourism into 3 sub groups: cycling holidays, holiday cycling and cycling day visits. This study focuses on cycling day visits, where tourists use organized cycling tours, outlined cycle routes or plan their own route, depending on experience.

Transport has an increasingly significant impact on the environment and health in terms of air and noise pollution. McClintock (2002) points out that also people’s quality of life is affected in ways of heavy road traffic and major transport infrastructure, since that can divide communities and reduce opportunities for social interaction. However, the speed, comfort and convenience of motorized transport, makes it a formidable competitor to cycling. ‘To make matters worse, cars have become the most potent symbol of the consumer society.’ (Tolley 2003, p.13) Another major factor for choosing motorized transport over bicycle is the fear of cycling, because of lack of good cycling infrastructure, such as cycling routes and cycle parking. (Horton et al. 2007) As a solution to the issues stated above, Forester (1994) suggests implementing bikeways in order to make cycling much safer and, therefore, the amount of cycling transportation would increase. In this matter Mundet & Coenders (2010) and Gobster (2005) stress the main benefits of implementing greenways and bicycle roads, which include healthy living and outdoor recreation, safe, inexpensive avenue for regular physical activity, alternative transportation, economic benefits for community’s ‘en route’, environmental benefits as well as a sense of place.

Even though, it is often claimed that the addition of cyclists to the traffic mix reduces highway capacity, delays motorists and increases trip times, or that the presence of cyclists causes turbulence in the traffic flow that persists downstream from its source (Forester 1994) there are still great benefits to cycling and for the whole community in that matter. McClintock (2002) identifies the benefits to public policy and individuals, such as reduced traffic congestion, road way cost savings, reduced parking problems and savings in the cost of providing and maintaining parking, greater and more equitable transport choice. As for the social and environmental benefits, he mentions reduced community severance and increased community interaction, which can result in safer streets. Some other benefits are stated by Pucher & Buehler (2008, p.496): ‘Cycling requires only a small fraction of the space needed for the use and parking of cars. Moreover, cycling is economical, costing far less than both the private car and public transport, both in direct user costs and public infrastructure costs.’ And as for the time consumed, Parkin (2011) believes that in congested conditions and over shorter distances, cycle-users will reach their destination more quickly than drivers.

In its main idea, ‘sustainable development embraces continued growth, but acknowledges the inequities of the past that still prevail.’ (Howie 2003, p.4) It operates at macro and micro levels, according to Liburd and Edwards (2010, p. 132), where ‘the macro level is about the development of social and economic policies that enhance environmental protections, social wellbeing and economical justice.’ This paragraph focuses on the macro level, analyzing the possible impact of cycling tourism in an urban destination in terms of economic, socio-cultural and environmental sustainability.

Economic impact. Generally, tourism may have both positive and negative impacts on a destination (Liburd & Edwards 2010, p.22), such as stimulating local production, generating investment in local businesses and increasing employment, but at the same time, raising prices of goods, services, housing and increasing costs of living and general economic dependency.In case of cycling tourism, Simonsen et al. (1998, p.145) state that ‘cycling tourists have a low daily expenditure and are not therefore economically attractive type of tourist compared to others’. Nevertheless, cycle tourists use local businesses and there is a greater likelihood that the money they spend stays in the local economy. (Sustrans 1999)

Socio-cultural impact. In terms of socio-cultural impact, Liburd & Edwards (2010, pp.23-24) mention fostering understanding and social change, preserving cultural identity and improving quality of life of locals, while increasing prostitution, drugs, crime and provoking commodification[1]. In their research on cyclists’ motivation Brown et al. (2009) conclude that even though the economic and ecological motivation instruments are important, the most important are the social aspects. Cycling tourists like engaging in this kind of a social activity, spending time with other cyclists with similar interests, or just being part of a collective. Furthermore, cycling tourism can help to encourage utility cycling, as well as to improve cycling provision for local people in general. Local community may rediscover cycling while on holiday or as a leisure activity, and therefore be encouraged to cycle more frequently for other purposes. By encouraging cycling tourism, it may also result in government providing an additional justification for investment in cycle provision. (Sustrans 1999)

Environmental impact. Environmentally, tourism may encourage conservation, preservation and beautification, but it still has a substantial carbon footprint, lead to pollution and recourse degradation. (Liburd & Edwards 2010, p.23)Nevertheless, cycling tourism is an environmentally sustainable form of tourism with minimal impact on the environment and host communities. (Sustrans 1999) It stands out as having many positive sustainability attributes. ‘Cycling places no demands on fossil fuel reserves and also can help to reduce unsustainable air and noise pollution generated by motor traffic.’ (McClintock 2002, p.8)

In the end it can be concluded that cycling has more positive than negative effects on a destination. Tourism destinations should focus more on sustainable tourism development, so cycling tourism might be a good option. Therefore the next part of this study concerns cycling tourism product and demand. In this research Riga has been chosen as the possible cycling tourism destination, so the research is focusing mostly on the evaluation of the cycling product in Riga and what could/should be done in order to improve it.

Cycling tourism demand. Respondents were asked if they had ever been on a cycling holiday, had a cycling city tour or not, would they want to (refer to Figure 1). The results show, that only 34% have been on a cycling holiday or tour (mostly Eastern Europe and Latvia). However 53% would love to go on a cycling tour and 37% on a cycling holiday.

|

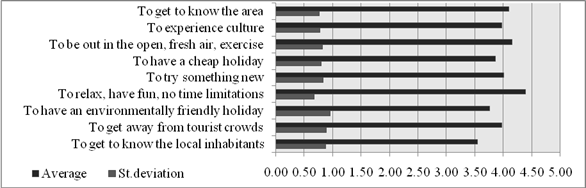

| Figure 1: Motivation for choosing a cycling holiday (Author) |

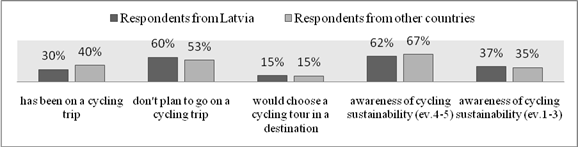

Regarding the main reasons for choosing a cycling holiday in the past or future, priority was given to leisure, followed by outdoor activity and exploring of new areas. The least important reasons were to get to know local inhabitants and having an environmentally friendly holiday (refer to Figure 1). In terms of sense of sustainability, the results between Latvian respondents and respondents from other countries are quite similar (refer to Figure 2). This proves that Latvia, although the sustainable ways of thinking are very new and not so popular yet, is still thinking in the way of sustainable development.

|

| Figure 2: Sense of sustainability in cycling - Latvia vs. other countries. (Author) |

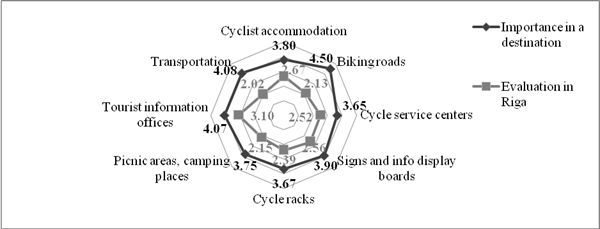

In the survey respondents were also asked to evaluate the importance of basic cycling facilities in an urban destination and then evaluate the quality of the same components in Riga. A great difference is noted in all the components, as Riga’s evaluation is lower than the general importance (refer to Figure 3). Further in this paper, all of these components are discussed briefly and referring to Figure 3, for the problem has been stated, but the solution is yet to be found.

|

| Figure 3: Comparison of evaluation between general importance and in Riga. (Author) |

Cyclist accommodation. The results show that cyclist accommodation is measured as being important (3.8 points out of 5), but this facility in Riga is graded as 2.67 only which is 1.13 points less than general evaluation.On 1 November 2011, there were five bicycle friendly hotels in Riga located close to the old town (in 4 km radius) and 4 of them were of the same price range (av.30-50 EUR per night). Cycling tourism is seasonal and, since most of the hotels in Riga are fully booked during the high season, there has been no special attempt on attracting cycling tourists. Then again smaller hotels, especially those located further than 4 km from the center and/or rated with 2 to 3 stars, are suffering from low capacity even during the high season. By creating some form of drying facility and secure storage for bicycles, these hotels could attract cycling tourists and increase their profit. Cycling tourists have their own means of transportation, so the distance does not matter, same for the luxury and price of a hotel - they prefer cheaper hotels, because they are not willing to pay more than 100 EUR per day. Accommodation in Riga is basically a private sector, but it has some tax benefits from the public sector (instead of 21% VAT it is 10%) in order to develop the hospitality sector in Latvia. For the small hotels to be able to create any cycling amenities, government could provide some basic funding for the expenses of construction. In this way government would help the hotels not only financially, but would also foster sustainable tourism development, possibly inspire other entrepreneurs to do the same and in this way popularize cycling as an alternative for motorized transport.

Bicycle roads. In Figure 3, biking roads were graded as the most important facility at a destination (4.50), while Riga is facing one of the lowest evaluations in this matter – only 2.13 points. The traffic on the roads in Riga is 12 times more intense, than in the rest of the country. Apart from that, Riga has a comparatively high number of registered vehicles in Europe (322 528), which has actually increased by 48.1% in the last 10 years. (Development program of Riga 2010) The positive aspect in this matter is that the municipality of Riga realizes the importance of bicycle roads in terms of sustainable development, so there is a Development Program for Bicycle-transport carried out. At present Riga has 42 km of bicycle roads. They were made as a part of a European Union (EU) project called EuroVelo 10, and 65% of funding was from the EU. The City Council is planning to construct roads up to 30 km and by year 2018 the bicycle roads are supposed to cover the main roads in Riga. (RDSD 2011) The new planned bike roads are going to be a part of the pedestrians’ pavement, not a part of roads. Two factors slowing down the process of constructing the bike roads are the lack of space on the roads and high expenses. (Liepina 2011)Eventually, it is up to local municipality to finish the construction of these bicycle roads as planned in the Development Strategy of Riga, and then the rating would increase. Bicycle roads would decrease traffic intensity, promote Riga as a sustainable tourism destination, decrease air and noise pollution, and encourage the cycling tourism development.

Cycle rentals, services and shops. The importance of bicycle rentals, services and shops is evaluated with 3.65, but the evaluation of Riga in this aspect is 2.52. There are exactly 33 bicycle related amenities in Riga - 20 bicycle services, 17 bicycle shops and 7 (+1 not mentioned) bicycle rentals, with additional 11 rental bicycle stands located throughout the city center (BalticBike). (Riga TIC 2011)One of the most common problems that tourists are encountering in terms of bicycle rentals is the lack of bicycles available for rent, because there are only 2 rentals in the center, so they run out of bicycles quite often. Other bike rentals are located far from the city center and staff does not speak English there. A possible solution to this problem could be simply expanding the “BalticBike” as to increase the bicycles available for rent and make further parts of Riga accessible by environmentally friendlier way of transportation.

Signs, info display boards and safety. This component of a cycling tourism product got 3.90 points regarding general importance, while 2.56 regarding quality evaluation in Riga.At present there are 30.2 thousand traffic signs on the streets of Riga, 313 traffic lights and 65 pedestrian crossings (Development program of Riga 2010). Nevertheless, the safety of cyclists is questionable, due to the accidents in the last years. In 2009 the total number of 10 cyclists died in accidents, in the year 2010 – 5. (Liepina 2011) In order to evaluate safety on roads, in the year 2002 a special department of Traffic Guidance was established whose main functions are: monitoring the situation on the roads, systematizing, analyzing it, and improving the necessary areas. (Development program of Riga 2010) Slowly the situation is improving, because the municipality of Riga is working on placing new signs for motorized and bicycle transport. (RDSD 2011) But while the improvements of cycling environment are still in process, all of the traffic participants should respect one another and take extra caution on the roads to avoid accidents.

Bicycle racks and parking places. Lack of cycling racks is another problem in Riga, as it is evaluated with 2.39, while the general importance is graded as 3.67. There are only few safe bicycle parking places in Riga, and only 10 of them in the old town, as most of the racks do not apply to the necessary safety requirements. (VeloRiga 2011) The criminal statistics inform that in the period from April to December 2010 there were 1047 bikes reported missing. (Liepina 2011) Cycling racks and parking places are essential features for developing cycling tourism, so this matter should be taken care of by both public and private sectors. The municipality should place more cycling racks (that meet the necessary safety standards) near monuments and cultural areas, while the private sector should place racks outside their institutions, especially for restaurants, shops and other leisure facilities. This would contribute to sustainable development, in terms of increasing the capacity of cyclists because of safe parking.

Picnic areas, campsites. In evaluating the picnic areas and campsites, general importance is 3.75, while in Riga it is graded with 2.15, which is a surprisingly low evaluation, since 25% of Riga constitutes parks and forests (Development program of Riga 2010). Nevertheless, there is only one campsite in Riga with 60 tent places, costing 5-6 EUR and located on an island in the river Daugava, which flows through Riga. (Riga city camping, 2011) As for the picnic areas, people are allowed to sit and have picnics in most of the city parks. No special picnic areas are designated in the center, but there are some parks, approximately 10 km away from the old town, with special picnic and bonfire areas, as well as the seaside 10-20 km away from Riga.

Tourist information centers. Tourist information centers (TIC) in Riga is the only facility that got a rating over 3 (3.10), while general importance of TIC is measured as 4.07. There are 3 official Riga tourist information centers (2 of them located in the old city, one at the Riga Coach Terminal, both operated by Riga Tourism Development Bureau (RTAB)) and one tourist information office in Riga airport, operated by the airport itself. In these centers tourists can get any information needed concerning cycling tourism: different routes around the city, order cycling city tours, find where the nearest bicycle rentals are and much more. Riga Tourism Development Bureau is the main institution in Riga promoting it, and popularizing the brand LIVE RīGA. 70% of RTAB is owned by Riga City Council. Thus it is more public than private facility. In terms of sustainable tourism development, LIVE RīGA focuses on commercializing the cultural life and entertainment, a tidy environment and high quality services characterized by cooperation between the municipality, entrepreneurs and society. ‘For guests of Riga it means well-managed infrastructure, a pleasant city environment, availability of information, friendly and honest service. For entrepreneurs the project means new possibilities for profit and promotion. The municipality will get increased income in budget, while residents will benefit most of all from the safe and enjoyable environment, new jobs and a bright future.’ (LiveRiga 2011)

Transportation. Transportation has received the lowest evaluation in Riga (2.02) while it has quite high general importance (4.08). It is probably due to the fact that, even though Riga public transport covers most of the city, it is not allowed to get on the transport with a bicycle, making train as the only exception. Nevertheless, in the Development Program of Riga (2010) it is planned to develop the train system in Riga, making it as the core of the transportation system. This would mean getting around Riga faster, polluting less, increasing the carrying capacity and being able to take bicycles to almost every part of the city.

To sum up, the following suggestions have been elaborated: 1) small and remote hotels could implement some cycling friendly facilities; 2) there should be more bicycle rentals in the center, as well as BalticBike could expanded the area it covers; 3) more cycling racks should be placed all over the city; 4) traffic participants should respect more one another, while the cycling roads are still under construction and signs are placed.

To summarize, the study revealed that the demand for cycling tourism in Riga has increased more than 2 times during the last years and therefore causes a slow development and expansion of cycling tourism in the city. Regarding cycling tourists’ motivation, sustainability is one of the least important issues, placing leisure, outdoor recreation and exploring of new areas as the main motivation. Still, the sense of sustainability is quite high, for 65% of the respondents evaluated sustainable development as important.

However, all basic components of the cycling tourism product of Riga are evaluated lower than the general importance in an urban destination. There is a lack of bicycle rentals in the center of the city, cycling on the roads is dangerous, because of possible accidents, there is a high number of stolen bikes registered, because of the lack of cycling racks and safe parking places. The positive aspect in this matter is that the municipality of Riga realizes the importance of cycling in terms of sustainable development, for new bicycle roads and traffic signs are being put out.

Eventually, it can be concluded, that cycling tourism can contribute to sustainable tourism development in Riga just by getting developed there. Popularizing cycling tourism will increase the usage of less motorized transport, diminish air and noise pollution, decrease the intensity of the traffic and improve the quality of life for the local people.

In order to foster the sustainable tourism development, public and private sector have to find an effective way of collaboration. It is up to city council to improve the environment for cycling and promote Riga as a sustainable tourism destination, while the private sector has to cooperate with the government, follow the basic requirements in sustainable environment and gain an understanding in it. Collaboration, respect and willingness to change are the main key factors for sustainable tourism development in Riga.

This study is based on the quantitative empirical data analysis and secondary data analysis. The author suggests that future research is carried out in the economic scale in terms of calculating the approximate costs of developing cycling tourism and comparing them with the possible gain of it. This requires more specific data on cycling tourism expenditure, which is not collected at the moment. In terms of researching demand, qualitative data would be necessary to estimate the demand in more detail, in order to understand, what has to be changed to develop sustainable tourism in Riga.

Brown, T., O’Connor, J., Barkatsas, A. (2009). Instrumentation and motivations for organized cycling: the development of the Cyclist Motivation Instrument (CMI). Journal of Sports Science & Medicine, 8(2), 211-218.

Development program of Riga years 2010 – 2013 (2010). City Council. viewed 6 November 2011, retrieved from http://www.rdpad.lv/uploads/rpap/programma_1.dala.pdf

Forester, J. (1994). Bicycle Transportation. A handbook for Cycling Transportation Engineers. 2nd edition. USA: Custom Cycle Fitments, 346pp.

Geske, A., Grīnfelds, A. (2006). Izglītības pētniecība [Research of Education]. Riga: LU Akadēmiskais Apgāds, 261pp.

Gobster, P.H. (2005). Recreation and leisure research from an active living perspective: Taking a second look at urban trail use data. Leisure Sciences, 27(5), 367–383.

Guba, E. (1990). The Alternative Paradigm Dialog. The Paradigm Dialog, Sage Publications, 17-27.

Horton, D., Rosen, P., Cox, P (2007) Cycling and Society. UK: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 205 pp.

Howie, F (2003). Managing the Tourist Destination. UK: Thomson Learning, 346 pp.

Lamont, M. (2009). Reinventing the Wheel: A Definitional Discussion of Bicycle Tourism. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 14(1), 5-23.

Liburd, J & Edwards, D (2010). Understanding the Sustainable Development of Tourism. Oxford: Goodfellow Publishers ltd, 256 pp.

Liepina, Z (2011). Velosipēdu ēra Rīgā ir sākusies [The era of bicycles has begun in Riga]. Kapitāls, June 2011, 66-69

LiveRiga, Riga Tourism Development Bureau (2011). For partners, viewed 1 November 2011, retrieved from http://www.liveriga.com/en/1145-for-partners

Lumsdon, L. (1996). Cycle tourism in Britain. Insights, March, 27–32, English Tourist Board, viewed 17 October 2011, retrieved from http://www.visitengland.org/insight-statistics/a-z/index.aspx

McClintock, H (2002). Planning for cycling: principles, practice and solutions for urban planners. Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing, 325 pp.

Mundet, L & Coenders, G (2010). Greenways: a sustainable leisure experience concept for both communities and tourists. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18( 5), 657–674.

Parkin, J. (2011). Training the traffic engineer to meet cycle-users' needs. Logistics & Transport Focus, 13(5), 58-59.

Pucher, J & Buehler, R (2008). Making Cycling Irresistible: Lessons from The Netherlands, Denmark and Germany. Transport Reviews, 28(4), 495–528.

RDSD, Traffic Department of Riga City Council (2011). viewed 8 November 2011, retrieved from http://rdsd.lv/?ct=velosatiksme

Riga City Camping (2011). viewed 6 November 2011, retrieved from http://www.rigacamping.lv/

Ritchie, B.W. (1998). Bicycle tourism in the South Island of New Zealand: planning and management issues. Tourism Management, 19(6), 567–582.

Simonsen, P, Jorgensen B & Robbins D (1998). Cycling Tourism. Denmark: Research Center of Bornholm, 231 pp.

South Australian Tourism Commission (2005). Cycle tourism strategy 2005–2009. Viewed 31 October 2011, retrieved from http://www.tourism.sa.gov.au/tourism/plan/cycley_tourism_strategy.pdf

Sustrans, (1999). Cycle Tourism. Information pack TT21, pp.1-20, viewed on 31 October 2011, retrieved from http://www.sustrans.org.uk/assets/files/Info%20sheets/ff28.pdf

Tolley, R (2003). Sustainable transport: planning for walking and cycling in urban environments, Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing, 713 pp.

Tourism Statistics of RIGA TIC, 2011(unpublished data, available in Riga TIC).

Traffic Department of Riga (RDSD) (2006). The planned bicycle roads in Riga. viewed 31 October 2011, retrieved from http://rdsd.lv/?ct=velosatiksme

VeloRiga, Latvian Cyclist Union (2011). Safe bicycle parking places in Riga. viewed on 31 October 2011, retrieved from http://www.veloriga.lv/?ct=velostavvietas

[1] Commodification – the process in which the final outcome of a product is solely defined by its economical value (Liburd & Edwards 2010, p.238)