|

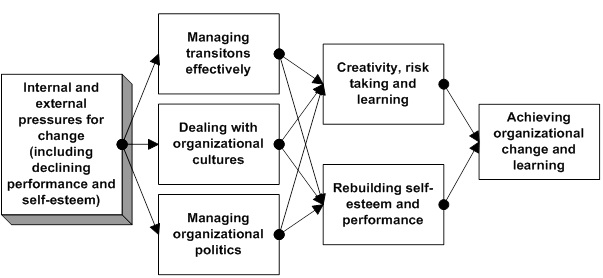

| Figure 1. Managing major changes (Carnall, 2003) |

Ieva Kalve, Dr.oec.

Turiba University, Latvia

Nicolae Sali, Ph.D.

Free International University of Moldova, Moldova

|

In these rapidly changing times, it is increasingly difficult to successfully lead an organization by using the classic management skills. There are lots of leadership and management theories available, but it is important to find how they are used in real life organizations. Managers’ knowledge or lack of it thereof not only influences the organizational results and the performance of employees, but also changes its thinking and models its behaviour. Employees are either stimulated to be open and innovative or, on the contrary, feel pressure to fulfil mindlessly directions and nothing else. The attitude, communication skills and empathy are traits that are very important in a leader (manager). The authors of this article have done a short summary of the most current organization management tendencies, while also doing empirical research that lets you compare the employees’ views on their managers in Latvia and Moldova – two developing countries that regained their independence in 1991 and that are still continuing their economic reorganization from a planned economy to a market economy, while taking up the challenges of the modern world and dealing with the reality of the global economic crisis. In conclusion, the authors have found the reasons for the similar and different results between the two countries and have formulated several suggestions. Keywords: management, change management. |

We are at the beginning of the second decade of the XXI century in terms of global financial and economic crisis. Unlike natural catastrophes, financial and economic crisis is due to human factors. The leaders of different levels have a role in getting out of this situation. (Cotelnic, 2011)

The current financial crisis is creating an increasing uncertainty about the economic future of world in general and Latvia as well. Overall, the crisis is not anything extraordinary; it is a recurring occurrence, and a lot of experience has been gained on finding solutions for these kinds of occurrences. But there are at least 2 tendencies because of which the crisis should be looked at closer in Latvia and other countries.

Taking into account the practical orientation of conferences in University Turiba, the purpose of this article is to give focussed information about the current management trends in two post-soviet countries: Latvia and Moldova.

Post-soviet countries have followed various paths in their transitions following the break-up of the Soviet Union. These diverging transitional paths provide a clear rationale for comparative studies into how historical circumstances and ongoing cross-cultural influences of the globalized business context amalgamate in different post-soviet countries. (Rees, Miazhevich, 2009)

The authors of this article were interested in the research done in 2009 by Rees and Miazhevich. It focused on the differences in socio-cultural change and business ethics in Estonia and Belarus. We can now say that certain parallels can be drawn between Latvia (which is similar to Estonia in many processes) and Moldova, which has a lot in common with Belarus. These countries represent considerably different cultural unities. They have different historical legacies in terms of religion, different discourses involving their soviet past and current national auto-portraits.

Since all three Baltic States regained their independence from the Soviet Union in 1990, they have experienced strong economic growth as well as technological advancement. They have implemented more radical reforms than other post-soviet countries and managed to reconnect their national economy to the western markets. In contrast, despite a push for privatization after the fall of the Soviet Union, the Belarusian government maintains a prevalent role in almost all sectors, which affects growth and productivity (Rees, Miazhevich, 2009); therefore, the situation in Moldova has more similarities with Belarus than with the Baltic countries.

At present, significant cultural variations between the different post-soviet countries are evident in their diverging reactions towards western managerial practices. According to several studies, the implementation of western-based practices engenders different, if not opposing, cultural reactions in these countries. (Rees, Miazhevich, 2009)

Rapid technological development substantially increases the amount of different kinds of information and knowledge available. It raises a lot of problems: how to find the right information or experience, how to incorporate it in everyday’s operations. Today there are few opportunities to shape organizational sustainability and success through conservative, old-fashioned hierarchical structures and other measures to preserve stability. (Kalve, 2008)

Terms like creativity, innovations, knowledge management, etc. are more and more often used even in Latvia, but different kinds of analysis done by researchers show that the application of them in the real management process often fails. Why? Results of the number of researches show that organizations need not only focus their attention on improving efficiency and productivity, but also on developing innovation mechanisms to stimulate knowledge creation, sharing and integration. What organizations need is a better understanding of how management in general and the knowledge management in particular are related to the innovation process and how it can be used to help foster innovation within organizations. (Kalve, 2009)

If the countries of the former Soviet bloc are to move towards establishing successful market economies, it is essential that their universities are able to design and deliver the highest quality management education. This education should stimulate innovative and independent ideas along with developing skills that can be applied to the practical context of management. It is important to know that this was no third-world situation – by the 1980s literacy rates were very high and within the entire Soviet bloc there was a strong and extensive network of institutions of higher education (Love, 2006), but, as Jackson (Jackson, 2002) points out, transitional economies of the former Soviet bloc, or emerging countries of Africa, South Asia, or South America may have shorter-term objectives.

Why are these differences important? As Battilana and Casciaro (Battilana, Casciaro, 2012) wrote in their article, scholars have long recognized the political nature of change in organizations. To implement planned organizational changes – that is, premeditated interventions intended to modify change – agents may need to overcome resistance from other members of their organization and encourage them to adopt new practices.

However, it is very important to remember that change implementation within an organization can be conceptualized as an exercise in social influence, defined as the alteration of an attitude of behavior by one actor in response to another actor`s actions. (Battilana, Casciaro, 2012)

The problems arise when managers educated in the Western tradition try to implement Western management and human resource practices in cultures that have a different history and locus of human value. The importance of cultural values to the conduct of organizational life is well established in literature (Jackson, 2002), but the authors of this paper tried to analyze similarities and/or differences in management of organizations in Latvia and Moldova.

In order to ascertain the real situation in the management methods used in organizations in Latvia and Moldova, an empirical pilot research (85 respondents in Moldova and 64 in Latvia) on management processes was carried out in January 2013. The specific situation of both countries (post-soviet, not strong market-oriented thinking and management traditions and knowledge combined with the global crisis) is still connected with the necessity of rapidly and effectively selecting classical and even the newest management principles and trends for application. Both quantitative and qualitative changes in opinions and processes are taking place.

Although changes are an integral part of life, there is a lack of understanding and resistance to change. It is important to understand that changes in a particular organization (or country) involve not only precisely defined goals and expectation achievement plans, but also a human dimension – human understanding and support or resistance to the manager`s expectations are a significant factor.

As Carnall (Carnall, 2003) points out, it is not possible to carry out one small change in an organization, a much broader view is necessary (see Figure 1).

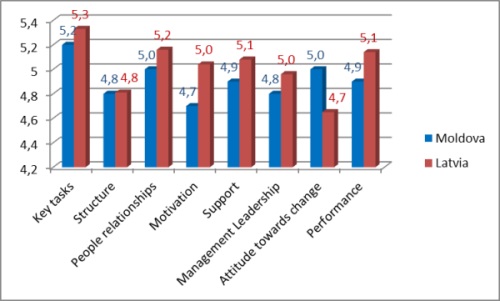

With all these aspects in mind, the authors of this article used an organizational diagnosis questionnaire developed by Carnall (Carnall, 2003) for getting initial/pilot empirical evidence on similarities or differences in management methods used in Latvia and Moldova. In the following questionnaire, eight areas are assessed (key tasks, structure, people relations, motivation, support, management leadership, attitude towards change, performance), each with five statements as shown on the check sheet that follows the questionnaire (see also Annex 1 and Annex 2). This questionnaire is designed to help determine how well an organization works in a number of related areas.

|

| Figure 1. Managing major changes (Carnall, 2003) |

Respondents are asked to respond to each of 40 questions on a Likert-type scale on the basis of “what I think” (1 – strongly disagree to 7 – strongly agree). Respondents (n=149) in their professional capacity are employees, different level managers in state and private organizations. The research does not include ordinary workers – unqualified or representatives of simple professions.

In order to interpret the results more deeply, one additional variable was used: the type of organization (state, private (owned by local entrepreneurs) and western-private (“western” owned or managed)). The questionnaires were anonymous, respondents did not risk being identified and it was also not necessary to fill the name of organization or city.

|

| Figure 2. Average rating of statement groups/areas |

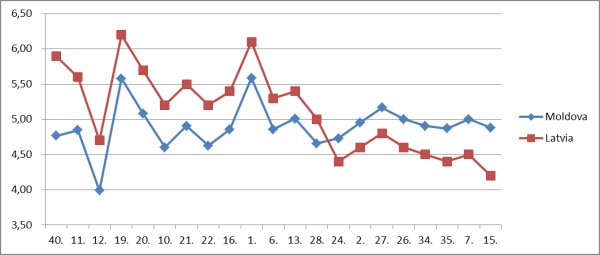

The highest average rating is for key tasks area – 5.3 for Latvia and 5.1 for Moldova. We can see that in 7 out of 8 groups’ evaluations made by Latvian respondents are higher. It is possible to explain this trend with a longer experience and more intense movement towards the “western management style”, but evaluations from Moldova are substantially higher in attitude towards change. It may show that right now Moldavians are more eager and ready to implement changes – because they clearly see what is done in some other (Baltic) post-soviet countries and success of their neighboring country Romania, the newest member of the European Union at the moment. For Moldova, there is a long way ahead if the country makes a clear decision to move towards the European Union, but the attitude towards change shows promising signs. Latvian result may be lower due to various reasons, but one of these – during past 20 years a lot of changes have been made (mostly – positive), but the recent crisis has hit Latvia hard, and together with some very disappointing government mistakes made in the recent past people may feel tired and not willing to change.

|

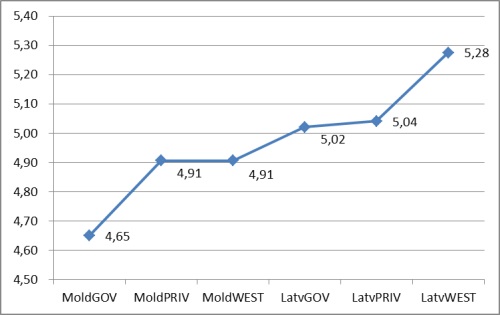

| Figure 3. Average rating curve by type of organization and country |

If we look at the average ratings based on organization type (state, private (owned by local entrepreneurs) and western-private (“western” owned or managed)), we can clearly see that the ratings in Moldova are lower across all groups (see Figure 3).

Difference is the lowest between overall evaluations in private organizations (0.11), and this is a positive signal. The highest difference is between “western” owned or managed organizations (0.37), and this may be explained in two ways:

In Moldova, there is a clear difference between evaluations of management methods used in governmental organizations (4.65) which is quite a low number and both kinds of private organizations – both get evaluation 4.91. The situation in Latvia is different – evaluations in governmental and locally owned private organizations are similar (5.02 and 5.04), while “western” organizations get a substantially higher evaluation – 5.28. The evaluations of governmental organizations also differ substantially – from 5.02 in Latvia to 4.65 in Moldova – there is a real place and need for improvements. From this point of view, we can conclude that foreign-owned companies in Latvia may be seen as initiators of the use of modern methods; and this trend in Latvia has been quite stable during the last 5 years as shown in research done by Kalve in previous years (see Kalve 2008, 2009, 2010).

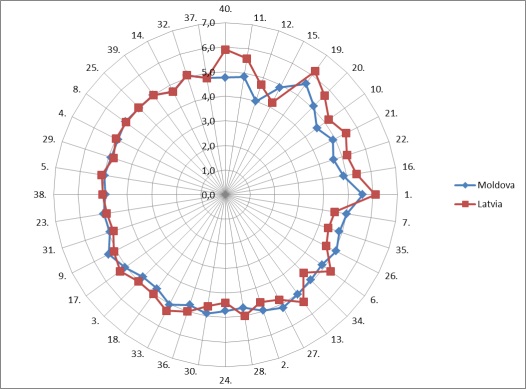

When analyzing the answers to each of the questions, a Radar chart was made for convenience, moving right to get from the questions with the most varied answers to the least ones (see Figure 4). You can see the full questionnaire in Annex 1.

|

| Figure 4. Evaluations sorted by difference and the country |

Figure 4 shows that answers to the individual questions are generally comparable and there is some dominance a (little bit higher evaluations) by Latvian respondents, but in some points the lines are crossing and Moldovan evaluations are higher or equal with Latvian ones.

The biggest difference is apparent in question 40 (people are always concerned to do a good job): 4.76 in Moldova and 5.9 in Latvia. This may correspond with findings of Gorton and colleagues: during the Soviet era, directors and workers derived mutual benefits from concealing true capacity, hoarding labor and just fulfilling the enterprise`s plan. In an environment of labor shortages and guaranteed markets, managers used informal mechanisms to reward and retain good workers given the absence of unemployment and meaningful wage differentials as mechanisms to discipline workers. This cultivated a paternalistic set of relations between enterprise managers and workers, which, it is argued, are being hollowed out of post-communist era. In Western market-based economies, the viability of paternalistic labor relations waned during the twentieth century as the state took on the role of providing universally available education, housing and health care, undermining the importance of company-based social services. (Gorton, Ignat, White, 2004)

In their research about Estonia and Belarus, Rees and Miazhevich also pointed out that their study reveals contradictory manifestations of mixtures of business norms in both Estonia and Belarus, which are conditioned by the merger of an autocratic bureaucratic soviet system with more participative and empowering forms of western management. The most persistent changes relate to moves from patriarchal and paternalistic types of relationship and low work motivation. (Rees, Miazhevich, 2009)

The second biggest difference (0.75) is in question 11 (I can always talk to someone at work if I have a work-related problem). It may show that people in organizations (all levels) do not understand the overall objectives or how their jobs fit into the whole company picture. They do not feel motivated by the work they do, partly, it appears, because of this latter problem. This finding has some connections with previous – employees in Moldova are not very interested in problem solving, looking for advice and getting it, they are concerned just about fulfilling everyday requirements and plans. This corresponds quite closely with the findings of Cotelnic and Jackson: Cooperation with foreign partners on international or domestic markets revealed discrepancies in knowledge of the local managers and those from the West. Another group of problems are similar to the ones in the West and deal with the changes which take place within organizations, the processes of globalization, and the implementation of modern communication technologies. Management professionalization – as a complex trend – involves essentially a change of vision and management approach that can synthesize the transition from traditional management into modern management (anticipatory, predictive, innovative, computerized, systemic, and international). (Cotelnic, 2011) Western managers and HR practitioners who work with affiliates in non-Western emerging countries should particularly be aware of differences in “locus of human value”. (Jackson, 2002)

In order to better see the differences between the countries, we have created Figure 5. It does not contain the questions where the difference between respondents’ answers was less than 0.3 (there were 19 such questions); therefore Figure 5 contains 21 questions, which have been sorted from the largest to smallest difference. The first 13 questions had a higher rating from Latvian respondents, while the last 8 were higher rated in Moldova. You can see the full set of questions in Annex 1.

The dynamics of the curves are similar; it indicates similar tendencies and evaluations of situations. By investigating the questions with the largest difference between groups/areas, we came to the conclusion that Moldavian respondents highly value organizational structure and the attitude to change, while Latvian respondents value motivation, support from the management and leadership qualities. We have already interpreted the attitude towards change before, but the positive evaluation of organization structure in Moldova is something that requires additional research, as researches done in Latvia in organizational structure show that it has been seen as inappropriate for years (see Kalve 2008, 2009, 2010).

There is a large drop off in the answers to question 12 (The salary that I receive is commensurate with the job that I perform). The difference between the countries is 0.71, the respondents in Moldova being substantially unhappier. Latvia also has salary related problems, as researchers Vintisa and Kalviņa (they had 38 000 respondents) have found out when to the question “What aspects of the existing performance appraisal system should be improved?” the two dominant answers were: setting the pay level – 49%, planning of professional development – 44%. (Vintisa, Kalvina, 2011). Jackson also points out that a distinction has been made in the strategic human resource management literature between hard and soft perspectives. The hard approach reflects a utilitarian instrumentalism. This sees people in the organization as a mere resource to achieve the ends of the organization. The soft developmental approach sees people more as valued assets capable of development, worthy of trust, and providing inputs through participation and informed choice. The two approaches are simply two poles of a continuum. (Jackson, 2002)

|

| Figure 5. Major differences in evaluations |

Even though the world is overwhelmed with the global scale finance crisis, people in organizations must be able to see and implement the novelties and innovative solutions in order to make their organizations competitive.

One of the ways to achieve the introduction of the changes in organizations is understanding the importance of the organization`s employees’ professionalism and necessity for changes that include both the management competences and orientation in the social culture, the skill of the competitors` analysis and the assurance oriented towards the outcome.

Kulberga points out that the employees’ education and training have to be considered both the lifestyle and a part of total corporative culture, but it is not the training just for the sake of a tick that has to be put just as a formal care of the employees’ development. A continuous learning and education system as well as the implementation processes of novelties and improvements inside the company have to become a daily necessity, where the implementers of changes have to be assured not by words but by the achieved outcomes and their assessment. (Kulberga, 2011)

Changes are never easy, but Merell`s suggestions may be really worth of consideration and use in both countries: Manager`s job is to get the unwilling to do the impossible for the ungrateful. It is a fact that change is a constant reality for any organization trying to survive and thrive in these turbulent and uncertain times. Companies highly effective at both communication and other change management activities are 2.5 times as likely to outperform their peers that are not highly effective in either area. The best organizations also said their leaders inspired confidence in the change, creating clarity among employees and fostering a sense of community. Good communication during change fosters understanding, aligns the organization from top to bottom and guides and motivates employees. Learning activities can help push a change initiative along, and they are worth attention. Why? Employees need to have the knowledge and skills necessary to adapt to change. Setting clear, measurable goals up front will help an organization head in the right direction and use resources efficiently. When organizations involve their employees in the design and implementation of change, they are more likely to be effective at change management and less likely to face employee resistance to change. (Merell, 2012)

Since both authors of this article come from Universities, it was not difficult to agree that Universities have a very important role in educating the current and prospective leaders; therefore special attention should be paid to the development or actualization of the curriculum, because it, according to Love, is an instrument for changing student behavior; its objectives are statements of ways in which knowledge, cognitive abilities, skills, interests, values and attitudes of students should change if the curriculum is effective. Curricula must be understood as embracing and helping to transmit the dominant social, political and economic values and priorities of a market economy – including assumptions about the nature of freedom, democracy and the social construct of Civil Society. (Love, 2006)

He also says, and the authors of this article wholeheartedly agree, that changes should start from within – from the staff and Universities: The faculties teaching economics and management would seem to be obvious candidates, or targets, for substantial change. Clearly, the changes in these faculties would involve their staff in re-writing old syllabuses or writing new ones – each on a focus, and a positive attitude, towards market economics and business. But how easy would it be for lecturers to re-orientate their values and beliefs to meet the demands of the new market-oriented economic systems? Under the old Soviet system of student learning and assessment, it was a common practice for the lecturer to dictate material that the student was expected to write down in detail. Then, to obtain a high grade in assessment, the student had to reproduce that material as near to the original as he or she could. There was little scope for students to demonstrate their individuality and intellectual imagination. But, of course, in the Soviet system such qualities as independent thought were not priority learning outcomes. Conformity of thought was the high priority. (Love, 2006)

The authors of this article met in autumn of 2012 when one of them (Kalve) spent a month, as part of the ERASMUS program, sharing her experience and knowledge with her colleagues in Free International University of Moldova. Since both authors represent private Universities, there were a lot of similarities, but a lot of differences were noticed as well, and they served as the basis of this pilot research and article. This collaboration should definitely be continued and expanded by getting more respondents in each country in order to see if the results of this research are a systemic tendency. The expanded research would not only let us understand the current situation and do some initial interpretation, similarly to how it has been done in this article, but it would also make it possible to create specific suggestions for both further collaboration and the recommended improvements in each country.

Battilana, J., Casciaro, T. (2012). Change agents, networks, and institutions: a contingency theory of organizational change. Academy of Management Journal, 2012, Vol.55, No.2, pp. 381–398.

Carnall, C. (2003). Managing Change in Organizations. Fourth edition. London: Prentice Hall.

Cotelnic, A. (2011). Management professionalization in Moldova: current status and future prospects. Review of General Management, June 1, 2011, Volume 13, Issue 1, pp. 89–94.

Gorton, M., Ignat, G., White, J. (2004). The evolution of post-Soviet labor processes: a case study of the hollowing out of paternalism in Moldova. International Journal of Human Resource Management, November 2004, Volume 15:7, pp. 1249–1261.

Jackson, T. (2002). The management of people across cultures: valuing people differently. Human Resource Management, Winter 2002, Volume 41, Issue 4, pp. 455–475.

Kalve, I. (2009). Inovāciju un radošuma veicināšana organizācijās (Encouraging innovations and creativity in organizations). Proceedings of the X International Scientific Conference „Komunikācijas vadība informācijas sabiedrībā”, organized by School of Business Administration Turiba, Latvia.

Kalve, I. (2008). Latvijas organizāciju gatavība zināšanu pārvaldības un inovatīvas darbības iespēju izmantošanai (Readiness for knowledge management in Latvian organizations). Proceedings of the IX International Scientific Conference „Darba tirgus sociālie un ekonomiskie izaicinājumi”, organized by School of Business Administration Turiba, Latvia.

Kalve, I. (2010). Vadības aktuālās problēmas – Latvija Eiropas un pasaules kontekstā (Current managementproblems in Latvia in the world and european context).Proceedings of the XI International Scientific Conference „Cilvēks, sabiedrība, valsts mūsdienu mainīgajos ekonomiskajos apstākļos”, organized by School of Business Administration Turiba, Latvia.

Kulberga, I. (2011). Professional competence of changes implementation in business management in Latvia. Organizacijuvadyba: sisteminaityrimai, 2011, Issue 57, pp. 51–62.

Love, C. Developing management education in the countries or the former Soviet bloc: critical issues for ensuring academic quality. Innovations in Educations and Teaching International, Vol.43, No.4, November 2006, pp. 421–434.

Merell, P. (2012). Effective Change Management: the Simple Truth. Management Services, Summer 2012, pp. 220–23.

Rees, C.J., Miazhevich, G. (2009). Socio-cultural change and business ethics in post-Soviet countries: the cases of Belarus and Estonia. Journal of Business Ethics, 2009, Volume 86, pp. 51–63.

Vintisa, K., Kalvina, A. (2011). Performance management of employees in public administration of Latvia and opportunities for its improvement. Journal of Business Management, 2011, No.4, pp. 185–192.

| Annex 1 |

|

The full questionnaire with questions in numerical order, average results by

country and the difference (Latvian average minus Moldovan average) |

| Statement | Average Score | Diffe-rence | ||

| Mold. | Latv. | |||

| 1. | I understand the objectives of this organization. | 5,59 | 6,10 | 0,51 |

| 2. | The organization of work here is effective. | 4,95 | 4,60 | -0,35 |

| 3. | Managers will always listen to ideas. | 4,74 | 5,00 | 0,26 |

| 4. | I am encouraged to develop my full potential. | 4,92 | 5,00 | 0,08 |

| 5. | My immediate boss has ideas that are helpful to me and my work group. | 4,99 | 5,10 | 0,11 |

| 6. | My immediate boss is supportive and helps me in my work. | 4,86 | 5,30 | 0,44 |

| 7. | This organization keeps its policies and procedures relevant and up to date. | 5,00 | 4,50 | -0,50 |

| 8. | We regularly achieve our objectives. | 5,04 | 5,00 | -0,04 |

| 9. | The goals and objectives of this organization are clearly stated. | 5,34 | 5,10 | -0,24 |

| 10. | Jobs and lines of authority are flexible. | 4,60 | 5,20 | 0,60 |

| 11. | I can always talk to someone at work if I have a work-related problem. | 4,85 | 5,60 | 0,75 |

| 12. | The salary that I receive is commensurate with the job that I perform. | 3,99 | 4,70 | 0,71 |

| 13. | I have all the information and resources I need to do a good job | 5,01 | 5,40 | 0,39 |

| 14. | The management style adopted by senior management is helpful and effective. | 4,69 | 4,70 | 0,01 |

| 15. | We constantly review our methods and introduce improvements. | 4,88 | 4,20 | -0,68 |

| 16. | Results are attained because people are committed to them. | 4,86 | 5,40 | 0,54 |

| 17. | I feel motivated by the work I do. | 5,05 | 5,30 | 0,25 |

| 18. | The way in which work tasks are divided is sensible and clear. | 4,73 | 5,00 | 0,27 |

| 19. | My relationships with other members of my work group are good. | 5,58 | 6,20 | 0,62 |

| 20.. | There are opportunities for promotion and increased responsibility in this organization. | 5,08 | 5,70 | 0,62 |

| 21. | This organization sets realistic plans. | 4,91 | 5,50 | 0,59 |

| 22. | Performance is regularly reviewed by my boss. | 4,62 | 5,20 | 0,58 |

| 23. | There are occasions when I would like to be free to make changes in my job. | 5,02 | 4,90 | -0,12 |

| 24. | People are cost conscious and seek to make the best use of resources. | 4,73 | 4,40 | -0,33 |

| 25. | The priorities of this organization are understood by its employees. | 4,98 | 5,00 | 0,02 |

| 26. | There is a constant search for ways of improving the way we work. | 5,00 | 4,60 | -0,40 |

| 27. | We cooperate effectively in order to get the work done. | 5,16 | 4,80 | -0,36 |

| 28. | Encouragement and recognition is given for all jobs and tasks in this organization. | 4,66 | 5,00 | 0,34 |

| 29. | Departments work well together to achieve good performance. | 4,89 | 4,80 | -0,09 |

| 30. | This organization’s management team provides effective and inspiring leadership. | 4,89 | 4,60 | -0,29 |

| 31. | This organization has the capacity to change. | 4,94 | 4,80 | -0,14 |

| 32. | The work we do is always necessary and effective. | 5,11 | 5,10 | -0,01 |

| 33. | In my own work area objectives are clearly stated and each person’s work role is clearly identified. | 5,02 | 5,30 | 0,28 |

| 34. | The way the work structure in this organization is arranged produces general satisfaction. | 4,91 | 4,50 | -0,41 |

| 35. | Conflicts of view are resolved by solutions which are understood and accepted. | 4,87 | 4,40 | -0,47 |

| 36. | All individual work performance is reviewed against agreed standards. | 4,72 | 5,00 | 0,28 |

| 37. | Other departments are helpful to my own department whenever necessary. | 4,80 | 4,80 | - |

| 38. | My boss’s management style helps me in the performance of my own work. | 4,88 | 5,00 | 0,12 |

| 39. | Creativity and initiative are encouraged. | 5,01 | 5,00 | -0,01 |

| 40. | People are always concerned to do a good job. | 4,76 | 5,90 | 1,14 |

| Annex 2 |

|

Questions sorted by their area, average results by country and the difference (Latvian average minus Moldovan average) |

| Area | Average Score | Difference | ||

| Moldova | Latvia | Latvia minus Moldova | ||

| 1. | Key tasks | 5.20 | 5.33 | 0.13 |

| 2. | Structure | 4.83 | 4.81 | -0.02 |

| 3. | People relationships | 5.01 | 5.16 | 0.15 |

| 4. | Motivation | 4.70 | 5.04 | 0.34 |

| 5. | Support | 4.90 | 5.08 | 0.18 |

| 6. | Management Leadership | 4.77 | 4.96 | 0.19 |

| 7. | Attitude towards change | 5.02 | 4.65 | -0.37 |

| 8. | Performance | 4.90 | 5.14 | 0.24 |