|

|

|

|

|

|

| Resorts on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea started to develop in the first half of the 19th century whilst these areas belonged to the Russian Empire. The multi-dimensional process of formation and development of the resorts has had a major influence on the regional development in Estonia. After the Baltic States regained their independence in 1991, and, especially, since their accession to the EU in 2004 and to the Schengen zone in 2008, the Baltic Sea has become almost an “inland sea” of the EU. It is in this context that Estonian coastal regions and destinations, with their own unique identity and characteristics, are seeking new visions and conceptual solutions for cooperation and development strategies. Integral to this vision will be the message of sustainability, and of harmonious and well-balanced co-existence of traditions and modern tourism in the face of 21st century’s challenges. The method of study is historical including the content analysis of written media, archive sources and statistics. The authors highlight that image, sense and spirit of tourism destinations created by the resort heritage are the keystones of utmost importance for solid regional symbolic capital as one of the fundamental quarantees for long-term competitiveness. Therefore, tourism is and will continue to be one of the main keystones of sustaining the development and entrepreneurship, which also integrates the economic, cultural and natural resources into a holistic and competitive service, product and supply. |

|

Key words: resorts, coastal tourism history, tourism regions, Estonia, Baltic Sea Region. |

One of the catalysts of the modern tourism development alongside with the scientific and industrial revolutions and enlightenment, which began in Britain in the 18th century and then spread all over Europe in the 19th century, became the collective „lure of the sea“ (Corbin 1995). By Corbin (1995) the sea and shore had come to be viewed as something intensely and sensuously pleasurable.The elitist seaside resort holidays and seabathing became increasingly popular and reached the Baltic Sea Region in the end of the 18th century– the oldest known continental seaside resort in Europe – Heiligendamm[1]– „Die weiße Stadt am Meer”[2]in 1793.

This paper aims to analyse through comparative historical approach the formation and transformation process of the core destinations and tourism regions of Estonia over the past 200 years and especially to focus on how the western coast developed a leading role in this process. The main objective is to outline the importance of major geopolitical, economic and political (administrative) changes which have had a decisive impact on Estonia’s seaside resort development, and highlight their role in the seaside resort formation and transformation process in Estonia’s tourism regions. The specific goal is to create a systematic periodization of the developmental process of the seaside resorts and to identify the main milestones and key factors influencing transformation at different stages. Also, to outline the main forces behind the continuity of the resorts as the core destinations and development engines of the regions in Western Estonia.

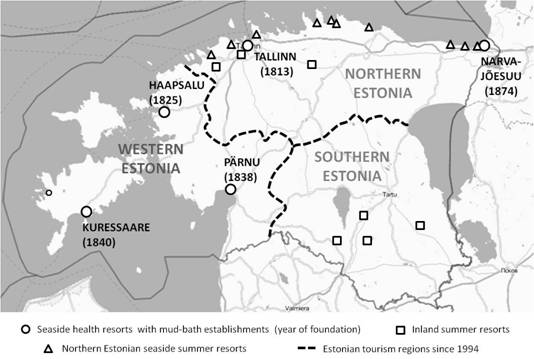

The 18-20th century history in Estonia including tourism development can be divided into periods between different wars, which shifted Estonia’s oritentation towards the East or West. (See Fig. 1.). Because of The Great Northern War (1700–1721) Estonia and Livonia became part of the Russian empire resulting in a rather peaceful and dynamic development during the 18-19th centuries.

|

| Figure 1: The changing periods, geo- and socio-political context of the development of Estonian seaside resorts (after Kask 2004; Saarinen and Kask 2008). The solid line and arrow imply the changing obstacles/limitations and orientations in tourism tourism development and markets. |

The first records of the summer guests and arranged seabathing in the Baltic Sea provinces of the Russian empire date back to the beggining of the 19th century. It was an uncertain and somewhat elitist start, while the local Baltic German and Russian elite took to the European aristocratic fashion of travelling, visiting health resorts and hiring summer residences.

The Estonian seaside towns[3] and coastal areas of a scenic beauty became popular summer holiday and bathing destinations already during the first half of the 19th century due to the healthy impact of the well-researched and applied local climatic, seawater and seamud treatment. According to Schlossmann (1939) the fame of the curative sea-mud in Estonia at the beginning was solely a feature of folkmedicine[4], from which it was later taken over into scientific medicine. Besides health and treatment issues the bathing guests made their decisions regarding the resorts on the basis of accessibility, attractive ambience and level and content of the social life.

The first generation of the Estonian resorts includes all historical coastal towns[5]- Tallinn/Kadriorg (1813), Haapsalu (1825), Pärnu (1838) and Kuressaare (Arensburg)(1840). According to the present knowledge the first public bathing establishment in Estonia was opened near Tallinn, at Kadriorg, in 1813. The palace and park belonging to the royal family got a new neighour – a bathing establishment erected in the territory of the neighbouring Wittenau summer estate by Georg Witte alongside with Bathing Salon added later[6]. All of this as an integrated entity became the first seaside resort in the Russian empire. During the next decades the Kadriorg Imperial Palace of Recreation and Amusement and Kadriorg as a whole became the most popular recreational and entertainment spot for the visitors and guests in Tallinn– the fashionable resort of the Russian elite (Nerman and Jagodin 2011).

The heyday of Kadriorg after the era of Peter the Great occured during the reign of Nicholas I (1825-55). During the late 1820s and early 1830s Kadriorg was being developed as one of the most important resorts in Russia and the palace was named as Imperial Palace of Recreation and Amusement in Catherinenthal. The1830s and 1840s were the peak of the heyday of Kadriorg (Kuuskemaa et al. 2010).

The popularity of „The waters of Revel[7]“ sustained the success of Kadriorg as a summer holiday destination and health resort also during the second half of the 19th century, and Kadriorg maintained the image of a charming sea resort until the end of the 19th century. By the turn of the century Kadriorg become the residential district of wealthy Tallinn bourgeoisie (Kuuskemaa et al. 2010).

Besides Tallinn Haapsalu became another persistent and innovative resort in the making. Although in 1824 58 summer guest families were registered there, 1825 is considered to be the official birthdate of the resort as the first mud treatment establishment was opened then. Haapsalu got a second mud treatment establishment in 1845 along with regular steamship connection with St.Petersburg, Riga, Tallinn and Kuressaare (http://www.muuseum... 2011).

Haapsalu became the favourite summer holiday destination of the royal family in Estonia during the 1850-ies. Alexander II visitied Haapsalu with his family in 1852, 1856, 1857, 1859 and Aleksander III did the very same in 1871, 1877 and 1880. Being the royal favourite ensured Haapsalu a competitive advantage – more visits and higher image - compared with other Estonian resorts. It was called “the first Northern resort in Russia” and the Russian Medical Board declared that “… as a health resort Haapsalu has not just local, but also all-Russian significance “ (Paras 2011).

Tallinn and Haapsalu based their initial stage and successful further development as resorts on a spontaneous process launched by the local private initiative. To compare, at the end of 1830-ies Kuressaare and Pärnu after their launch as resorts were far less successful in visitor flows and market awareness.

Similarly as in Europe, the railway network became the key developmental factor in Russia during the 19th century. St.Petersburg-Tallinn-Paldiski railway was opened in 1870, and it significantly improved the accessibility of the Northern Estonian coastal areas[8].

In adddition to the first generation of the resort towns, Narva-Jõesuu (1874) entered the market as a resort formed on the basis of the neighouring fishing villages - likewise the resorts of Riga-Strand[9]. The seaside resort with a beautiful sandy beach just within a 4-hour train trip from St.Petersburg became almost instantly very popular.

Pärnu and Haapsalu being located on the Western coast got the railway connections later – Pärnu in 1896 and Haapsalu in 1904 (Volkov 1980). Along with quite a dense road network and regular maritime connections the Estonian resorts were ready for the next dynamic developmental stage in the last decades of the19th and the beginning of the 20th century.

Before WWI the health treatment oriented resorts Pärnu (max 2500 visitors)[10], Haapsalu (~4000 to max ~8000) ja Kuressaare (~3000-4000) couldn’t compete with leisure resorts such as Riga/Jurmala (~60000) and Narva-Jõesuu (~10000-14000). Still, in Russia Pärnu, Haapsalu and Kuresaare had a very high repute as coastal resorts with modern treatment facilities, attractive ambience and hospitable communities.

After WWI the Republic of Estonia positioned itself as part of the integrated Northern European economic and cultural space. During the first half of the 1920-ies the summer leisure and holiday-related activities developed fast and at the beginning of the decade the European beach culture and fashion – the so-called public unisex (no longer women-only or men-only) beaches and the cult of sunbathing and recreational and social beach activities – reached Estonia, too.

The first public unisex beaches were opened in Tallinn (Pirita) in 1923 and Pärnu (Raeküla) in 1924 (Kivimäe et al. 1998). Beach recreation and holidays along with sunbathing became favoured by Estonians as a fashionable and healthy summertime activity. Due to that also the geography of the summer resorts spread, and in addition to the established seaside resorts along the Western and Northern coasts (beside Narva-Jõesuu Võsu and Käsmu should be mentioned) the lake- and riverside inland resorts in the Southeastern counties (Tartu, Võru and Petseri) sprung up (Prümmel et al. 1933).

Onwards from the end of the 1920-ies the new age of functionalism in the resort architecture was entering the pre-WWI resort milieu. The main principles of functionalism – the abundance of light, air and sunshine and promotion of healthy lifestyles – matched the modern trends in beach culture (Kalm 2002). Most of all the new bathing architecture had impact in Pärnu.

Already at the beginning of the 1920-ies the first foreign guests, mostly from Finland, Scandinavia, Latvia and Germany, visited the Estonian resorts. The most favoured resorts among the foreigners became The Summer Capital Pärnu[11] and Narva-Jõesuu. Still, also Haapsalu as the so-called „resort of health and peace“ and Kuressaare as the so-called „old health town“ were popular among the foreigners during the 1930-ies (Prümmel et al. 1933). Besides the four major resorts and the holiday spots on the Northern coast the inland summer holiday resorts (for example Elva) (Kuurordist ... 1937) were also being discovered by mostly domestic visitors.

While during the Russian empire the resorts in Estonia were depending mostly on the local private initiative and municipalities along with the marketing and sales, the state took a leading role between WWI and WWII not only in the marketing of Estonia as a destination, but also in its strategic development and management. By the end of 1930-ies The Ministry of Social Affairs and the Institute of Nature Conservation and Tourism managed in cooperation with the enterprises and municipalities to generate an image of Estonia as a safe and hospitable destination country with a modern tourism management.

The Estonian resorts compiled optimistic plans and drafted new developments along with the preparations to host alongside with their Baltic neighbours the visitor flows related to the Olympic Games in Helsinki to be held in 1940. However, WWII and its aftermath changed it all for decades.

|

| Figure 2: Estonian resorts in 1939 (after Schlossmann 1939) and Estonian tourism regions since 1994. |

The post-WWII Soviet period brought along imminent major changes also in the resorts in question. The state took over all the assets and facilities and the management was handed over to the Central Office of the Soviet Trade Unions headquartered in Moscow. The local municipalities became the sub-contractors within the Moscow-run health resort system and had almost no say in marketing or PR of their resorts.

By the 1950-ies Pärnu and Haapsalu as former summer resorts were transferred into all-year-round sanatorium-based health resorts run as part of the Soviet centralized system. The patients were arriving from all over the Soviet Union and for most of the numerous guests Estonia meant Soviet Abroad as close to the Western experience as possible without leaving USSR. In the 1960-ies besides the state-run sanatoriums the agricultural co-operative system set up sanatoriums of its own in Narva-Jõesuu, Pärnu and Saaremaa (Eesti NSV... 1963).

The rather intense development of the Estonian health resorts was based quite a lot on quantity continued during the 1970-ies, but stagnated along with the rest of the Soviet system during the 1980-ies. The production line of the Soviet fordistic health tourism became to a standstill after a certain period of prosperity and maturity (Kask 2009b).

In the 1950-ies also the former summer vacation resorts saw a certain re-start – this time in the Soviet context. Along with the domestic holiday-makers the vacationers from the rest of the Soviet Union started to flow in and similarly to the 19th century the Estonian summer vacation resorts became popular among the educated and creative circles of Leningrad and Moscow. Although the Western Estonian islands and Northern Estonian coast were restricted access areas due to the Soviet Union state border, seaside mass vacation boomed in the 1960-70-ies.The non-organized or the so-called "do it yourself" holidaymakers were accommodated mostly in the rented facilities provided by the locals (Kask 2009a; 2009b; Järs 2009). Due to this there is no adequate statistics about the summer vacationer flows covering the Soviet period in Estonia.

By the end of the 1980-ies the Estonian resorts and vacation destinatons faced a serious dilemma – whether to follow the mass tourism track led by the centralized Soviet system or choose a different option of one’s own paying more attention on the sustainable and well-planned protection and development of the local resort traditions and resources along with the quality and strategic competitiveness? These and many other issues were to be solved by the Estonian resort and tourism stakeholders themselves as learning by doing.

Leaving the deeply stagnated Soviet political and economic system meant also for the resorts and tourism industry re-focusing in the new market context. One of the most acute issues was deciding who and how should plan and implement tourism sector development and what kind of roles would public and private sectors play while participating in the processes to be launched both on the domestic and international level?

In spite of that in the domestic context the tourism development in the first half of the 1990-ies was hectic and mostly based on the local initiatives tourism became a stimulation agent of the transition process (Jarvis and Kallas 2006). As an example of this the regional tourism umbrella organizations were set up – first in the Western Estonia and then in the North and South as well forming the regional umbrella pattern existing even today (See Fig.2.). The three Western Estonian historical resort towns – Pärnu, Haapsalu and Kuressaare - became the core destinations within the counties in question based on tourism resources, knowhow and local governance. The long-term and deep-rooted hospitality tradition provided a clear competitive edge during the transition period, which meant more loyal visitors at the historical seaside resorts.

Restoration of the seaside resorts of North Estonia started only at the beginning of the 2000s in Toila and Narva-Jõesuu (Kask and Raagmaa 2010).

Similarly to the early 1920-ies by the beginning of the 1990-ies the Eastern (Soviet) market collapsed and after the Soviet period Estonia had to shift its focus once more to the West - Finland, Sweden and Latvia – and to position itself as part of the integrated Northern European economic and cultural space. This meant, that once again the Baltic Sea Region was the home ground for the Estonian tourism.

After the Baltic States regained their independence in 1991, and, especially, since their accession to the EU in 2004 and to the Schengen zone at the end of 2007, the Baltic Sea has become almost an “inland sea” of the EU. In this situation the “new” BSR seaside destinations with their own unique identity and characteristics are looking for new creative and innovative ideas.

|

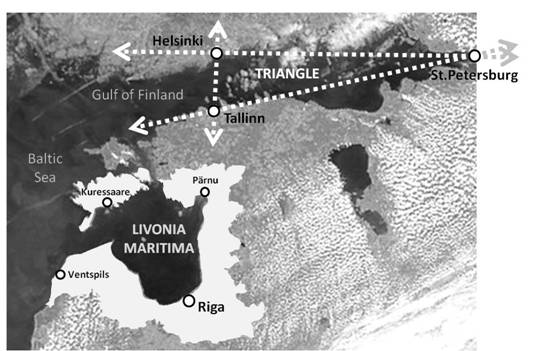

| Figure 3: New regional approaches. Livonia Maritima (since 2007) and Tallinn-Helsinki-StPetersburg triangle. |

Estonian seaside resorts and their hinterlands have become the scene for a multitude of alternative activities, creating the need for well coordinated integrated destination management practices. Therefore, Estonian West Coast seaside resorts as core destinations and development engines of the regions are looking for new regional approaches, which would also cross the sea and the state borders – such as Livonia Maritima in cooperation with Latvian partners (http://www.livoniamaritima.eu/) and Gulf of Finland Tourism Region (the so-called Tallinn-Helsinki-St.Petersburg triangle) in cooperation with Finnish and Russian partners (See Fig. 3.), all this within the dimensions of the present Central Baltic INTERREG Programme (http://www.centralbaltic.eu/... 2011) as the regional cross-border co-operation format relying on the economic and cultural space where Estonia, its tourism regions and resorts have been constantly re-focusing over the centuries.

The story of Estonian tourism leans on the so-called three whales – seaside resort development dating back to 18th century Britain, dacha (now seasonal or year-round second homes, initially small estates in the country) traditions dating back to 18th century Russia and heritage and traditions of folk medicine using local natural resources for hundreds of years in the Western Estonia.

The 200 years or so in question can be divided into 4 main periods, which represent the re-occuring pattern of re-focusing towards either East or West in the Baltic provinces related to the Russian empire during the 19-20th centuries. All the related geopolitical factors, national and local policies have had a major impact on the development process and sustainability of Estonian tourism.

The main factor which crucially influenced the tourism development in Estonia is the formation and transformation process of the first generation (also in the context of the Baltic Sea Eastern Rim) of Estonia’s seaside resorts – historical harbour and coastal towns such as Tallinn, Haapsalu, Pärnu and Kuressaare. Throughout this process they turned into the most competitive and sustainable core destinations, even trend-setters of Estonia’s tourism regions, and have had a major impact on the tourism development on a regional level.

So far the story of Kadriorg in Tallinn as the first Estonian resort has not been researched properly. Still, hundred years (1813-1914) of the prime resort in the Russian empire allow to analyze it as a case by using the classical Butler model of tourist destination development.The classical aspect is underlined by the similarity with the seaside of resorts in England and Europe, where also the visits of royalty, nobility and social elite, development of transportation and industry had major impact on the resorts. At the same time the developing transportation and industry caused the downfall and the end of the resort in Kadriorg. Since then the resort traditions have been sustained by the coastal towns of Western Estonia and Narva-Jõesuu.

Resorts – local community, seasonal visitors and the relations between the two groups – have been in a constant change. The long-term sustainability of the resort development relies heavily on how well the local community is able to use the local resources - economic, cultural and social capitals while being flexible in adapting to the changes. Therefore, creative local governance and deep-rooted hospitality practices can be considered as important factors in securing sustainability, which carries the message of the high-value historic milieu due to the harmonious and well-balanced co-existence of traditions and modern tourism trends.

Image, sense and spirit of tourism destinations created by resort heritage are the keystones of utmost importance for solid regional symbolic capital and/as one of the basic quarantees of a long-term competitiveness.

Corbin, A. (1995). The Lure of the Sea. The Discovery of the Seaside in the Western World 1750-1840. London pp. 57-96.

Eesti NSV kuurordid.(1963). Compiled by Vanker, H.; Veinpalu, E. and Vernik, L. Tallinn: Eesti Riiklik Kirjastus. pp 74-122.

Eesti tervismuda- ja merekuurordid: Haapsalu, Kuressaare, Pärnu, Narva-Jõesuu, Võsu, Loksa, Käsmu, Pirita jt. (1923). Compiled by Prümmel, J. Tartu: K/Ü „Loodus“.

Gustavson H. (1979). Tallinna meditsiin XIX sajandist kuni 1917.a.Tallinn: Valgus, pp 186-202.

http://b2b.tmv.de/balticseatourism/category/maritime/ (accessed 12.12.2011).

http://www.centralbaltic.eu/images/stories/imagebrowser/Maps/CB_new_map.jpg (accessed 12.12.2011).

http://www.livoniamaritima.eu/ (accsessed 13.12.2011).

Jarvis, J. and Kallas, P. (2006). Estonia – switching Unions: Impacts on EU membership on tourism development. In Hall, D., Smith, M. and Marciszweska, B. (eds.). Tourism in the New Europe: the Challenges and Opportunities of EU Enlargement. Wallingford: CABI, pp 154-169.

Järs, A. (2009). Suvituselu ja rannakultuur nõukogude ajal. In Reis [nõukogude] läände. Kuurortlinn Pärnu 1940-88. Journey to the [Soviet] West. Resort town of Pärnu during 1940-88. Compiled by Kask, T., Vunk, A. Pärnu: Pärnu Linnvalitsus, pp 109-119.

Kalm, M. (2002). Eesti 20.sajandi arhitektuur [Estonian 20th century architecture]. 2nd edition. Tallinn: Sild, pp 158-170.

Kasekamp, A. (2011). Balti riikide ajalugu. Tallinn: Kirjastus Varrak.

Kask, T. (2004). Resort of Pärnu – the heritage, which generates today’s success story and new trends of the Summer Capital of Estonia. Paper presented at the IGU Conference „Resent Trends in Tourism: The Baltic and the World. University of Greifswald, 20-24 June.

Kask, T. (2007). Pärnu: From Fortress Town to Health Resort Town. Pärnu: Pärnu Town Government.

Kask, T. (2009a).Pärnu kuurort 1940-1955. Nõukoguliku kuurordi kujunemisaastad. InReis [nõukogude] läände. Kuurortlinn Pärnu 1940-88. Journey to the [Soviet] West. Resort town of Pärnu during 1940-88. Compiled by Kask, T., Vunk, A. Pärnu: Pärnu Linnvalitsus, pp 39-59.

Kask, T. (2009b).Pärnu kuurort 1956-1988. Nõukoguliku kuurordi õitseng, küpsus ja stagnatsioon. In Reis [nõukogude] läände. Kuurortlinn Pärnu 1940-88. Journey to the [Soviet] West. Resort town of Pärnu during 1940-88. Compiled by Kask, T., Vunk, A. Pärnu: Pärnu Linnvalitsus, pp 89-107.

Kask, T. and Raagmaa, G. (2010). The spirit of place of West Estonian resorts. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift – Norwegian Journal of Geography. Vol. 64, pp 162-171.

Kivimäe, J., Kriiska, A., Põltsam, I. and Vunk, A. (1998). Merelinn Pärnu. Pärnu: Pärnu Linnavalitsus, pp 159-161.

Kuurordist kuurorti. (1937). Magazine „Maret“, July, Tartu: Maret, pp 206.

Kuuskemaa, J., Murre, A., Kalm, M. and Polli, K. (2011). Kadriorg. Lossi lugu. Palace’s story. Tallinn: Eesti Kunstimuuseum. Kadrioru Kunstimuuseum, pp 127-165.

Läänemaa Muuseum. Kronoloogia 1800. http://www.muuseum.haapsalu.ee/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=542:1800&catid=211:1800&Itemid=380 (accessed 10.12.2011).

Nerman, R. and Jagodin, K. (2011). Jalutaja teejuht. Kadriorg. Tallinn: Solnessi Arhitektuurikirjastus, pp 38-40.

Paida, H. (1962). Transpordi areng Eestis kapitalismi tingimustes. Eesti Geograafia Seltsi aastaraamat. Tallinn, 244 pp.

Paras, Ü. (2011). St. Peterburg - Haapsalu, in: www.haapsalu.ee/index.php?lk=225 ( accessed 30.11.2011).

Petersone, A. (2004). Развитие жилого пространство города. In , Cлава, П. (ed.) Юрмала. Природа и культурное наследие. Riga: Neputns, pp 77-115.

Prümmel, J., Rahamägi, H. and Raudsepp, V. (eds.). (1933). Eesti kuurortide käsiraamat. Tallinn: Kirjastus „Idee“, pp 5-13.

Saarinen, J. and Kask, T. (2008). Transforming tourism spaces in changing socio-political contexts: The case of Pärnu, Estonia, as a tourist destination. Tourism Geographies, 10(4), pp 452-473.

Schlossmann, K.(1939). Estonian curative-sea-muds and seaside health resorts. London: Boreas Publishing Co., Ltd., pp 5-42.

[1] Heiligendamm is part of the town Bad Doberan in the state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. http://b2b.tmv.de/balticseatourism/category/maritime/

[2] White town by the sea

[3] Here and hereinafter – 19century Estonian and Livonian town located on the territory of the present-day Republic of Estonia.

[4] According to Schlossmann (1939) on the islands of Saaremaa, Hiiumaa and on the coast of Haapsalu the use of sea-mud for curative purposes has been handed over as a tradition from generation to generation.

[5] With exception of Paldiski being awarded the town status in 1783 (Volkov 1980).

[6] Bathing Salon or Casino was built in 1825 for social entertainment (Nerman and Jagodin 2011).

[7] Ревелъ – The Russian name for Tallinn during the Russian empire.

[8] Thanks to the construction of the St. Petersburg-Paldiskirailway line and Tallinn commercial port Tallinn ranked the third harbour in total foreign trade turnover in Russiaafter St. Petersburg and Odessa (Paida 1962). The negative environmental impact caused by the rapid development of the port and the industry had also damaging influence on the reputation and further development of Tallinn as a seaside resort (Gustavson, 1979).

[9] Beach of Riga (in Latvian Rīgas Jūrmala) consisted of many different former fishing villages-based resorts West of the Daugava estuary. Dubulti (1814) and Kemeri(1838) should be mentioned in the context of the first generation of Livonian resorts (Petersone 2004).

[10] Maximum number of visitors during the summer season. In comparison to the statistics provided by Pärnu other Estonian resorts provided very rough and optimistic estimates without any references or sources.

[11] About 60% of the 8000 summer visitors, who stayed for longer than a week in Pärnu were foreigners in the summer of 1939 (Kask 2007).

|

Liga Freivalde, Silvija Kukle MECHANICAL PROPERTIES OF HEMP FIBRES AND INSULATION MATERIALS |

Heinz-Axel Kirchwehm OFFSET OBLIGATIONS – A CHALLENGE FOR SMALL AND MEDIUM ENTERPRISES (SME) |

|